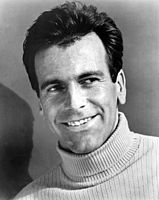

Maximilian Schell (8 December 1930 – 1 February 2014) was an Austrian-born Swiss film and stage actor, who also wrote, directed and produced some of his own films. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor

for the 1961 American film Judgment at Nuremberg, his second acting role in Hollywood. Born in Austria, his parents were involved in the arts and he grew up surrounded by acting and literature. While he was a child, his family fled to Switzerland in 1938 when Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany, and they settled in Zurich. After World War II ended, Schell took up acting or directing full-time. He appeared in numerous German films, often anti-war, before moving on to Hollywood. Schell was top billed in a number of Nazi-era themed films, as he could speak both English and German. Among those were two films for which he received Oscar nominations: The Man in the Glass Booth (1975; best actor), where he played a character with two identities, and Julia (1977; best supporting actor), where he helps the underground in Nazi Germany. His range of acting went beyond German characters, however, and during his career, he also played personalities as diverse as Venezuelan leader Simn Bolvar, Russian emperor Peter the Great, and scientist Albert Einstein. For his role as Vladimir Lenin in the television film Stalin (1992) he won the Golden Globe Award. On stage, Schell acted in a number of plays, and his was considered “one of the greatest Hamlets ever.” In Schell’s private life, he was an accomplished pianist and conductor, performing with Claudio Abbado and Leonard Bernstein, and with orchestras in Berlin and Vienna. His elder sister, Maria Schell, was also a noted Hollywood actress, about whom he produced the documentary My Sister Maria, in 2002.

Schell was born in Vienna, Austria, the son of Margarethe (ne Noe von Nordberg), an actress who ran an acting school, and Hermann Ferdinand Schell, a Swiss poet, novelist, playwright and pharmacy owner. His parents were Roman Catholic. Schell’s father was never enthusiastic about young Maximilian becoming an actor like his mother, feeling that it could not lead to “real happiness.” However, Schell was surrounded by acting in his early youth: I grew up in a theatre atmosphere and took it for granted. I remember the theatre, as a child, the way most people remember their mother’s cooking. Acting was all around me, and so was poetry. I made my debut in the theatre at the age of three, in Vienna . . . The Schell family was forced to flee Vienna in 1938 to get “away from Hitler” after the Anschluss, when Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany. They resettled in Zurich, Switzerland. In Zurich, Schell “grew up reading the classics,” and when he was ten, wrote his first play. Schell recalls that as a child, growing up surrounded by the theatre, he took acting for granted and didn’t want to become an actor at first: “What I wanted was to become a painter, a musician, or a playwright,” like his father. Schell later attended the University of Zurich for a year, where he also played soccer and was on the rowing team, along with writing for newspapers as a part-time journalist for income. Following the end of World War II, he moved to Germany where he enrolled in the University of Munich and studied philosophy and art history. During breaks, he would sometimes return home to Zurich or stay at his family’s farm in the country so he could write in seclusion: My father and my uncle hunt deer there, but I do not like to hunt. I like to walk through the forest by myself. In 1948 and 1949, when I wrote part of my first novel, which I have never shown to anyone, I isolated myself in one of the hunting cabins for three months, without a telephone, without electricity, with heat only from a large open fireplace. Schell then returned to Zurich, where he served in the Swiss Army for a year, after which he re-entered the University of Zurich for another year, and later, the University of Basel for six months. During that period, he acted professionally in small parts, in both classical and modern plays, and decided that he would from then on devote his life to acting rather than pursue academic studies: I then decided, either you are a scientist or an artist. . . . To me it is much more important . . . to admire and feel and be stimulated and inspired. . . Art comes out of chaos, not out of a mechanical analyzing. So as soon as I made up my mind, there was no sense any more in continuing to study and in getting a degree. It is like an award; it does not mean anything in itself. . . . A university degree is just a title. I don’t think an artist should have a title. It was time for me to concentrate on acting. Schell began acting at the Basel Theatre. Schell’s late elder sister, Maria Schell, was also an actress, as are their two other siblings, Carl and Immy (Immaculata) Schell.

Schell’s film debut was in the German anti-war film Kinder, Mtter und ein General (Children, Mothers, and a General, 1955). It was the story of five mothers who confronted a German general at the front line, after learning that their sons, some as young as 15, had been “slated to be cannon fodder on behalf of the Third Reich.” The film co-starred Klaus Kinski as an officer, with Schell playing the part of an officer-deserter. The story, which according to one critic, “depicts the insanity of continuing to fight a war that is lost,” would become a “trademark” for many of Schell’s future roles: “Schell’s sensitivity in his portrayal of a young deserter disillusioned with fighting became a trademark of his acting.” Schell subsequently acted in seven more films made in Europe before going to the U.S. Among those was The Plot to Assassinate Hitler (also 1955). Later in the same year he had a supporting role in Jackboot Mutiny, in which he plays “a sensitive philosopher,” who uses ethics to privately debate the arguments for assassinating Hitler. In 1958 Schell was invited to the United States to act in the Broadway play, “Interlock” by Ira Levin, in which Schell played the role of an aspiring concert pianist. He made his Hollywood debut in the World War II film, The Young Lions (1958), as the commanding German officer in another anti-war story, with Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift. German film historian Robert C. Reimer writes that the film, directed by Edward Dmytryk, again drew on Schell’s powerful German characterisation to “portray young officers disillusioned with a war that no longer made sense.” In 1960, Schell returned to Germany and played the title role in William Shakespeare‘s Hamlet for German TV, a role that he would play on two more occasions in live theatre productions during his career. Along with Laurence Olivier, Schell is considered “one of the greatest Hamlets ever,” according to some. Schell recalled that when he played Hamlet for the first time, “it was like falling in love with a woman. … not until I acted the part of Hamlet did I have a moment when I knew I was in love with acting.” Schell’s performance of Hamlet was featured as one of the last episodes of the American comedy series Mystery Science Theater 3000 in 1999. In 1959, Schell acted in the role of a defense attorney on a live TV production of Judgment at Nuremberg, a fictionalized re-creation of the Nuremberg War Trials, in an edition of Playhouse 90. His performance in the TV drama was considered so good that he and Werner Klemperer were the only members of the original cast selected to play the same parts in the 1961 film version. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor, which was the first win for a German-speaking actor since World War II. After also winning the New York Film Critics award for his role, Schell recalled the pride he felt upon receiving a letter from his older sister, Maria Schell, who was already an award-winning actress: I received the most wonderful letter from Maria. She wrote, ‘Now, when you have my letter in your hand, a beautiful day is coming for you. I will be with you, proud, because I knew such recognition would come one day, leading to something even greater and better. . . . not only because you are close to me but because I count you among the truly great actors, and it is wonderful that besides that you are my brother.’ Maria and I are very close. According to Reimer, Schell gave a “bravura performance,” where he tried to defend his clients, Nazi judges, “by arguing that all Germans share a collective guilt” for what happened. Biographer James Curtis notes that Schell prepared for his part in the movie by “reading the entire forty-volume record of the Nuremberg trials.” Author Barry Monush describes the impact of Schell’s acting: Again, on the big screen, he was nothing short of electrifying as the counselor whose determination to place the blame for the Holocaust on anyone else but his clients, and brings morality into question. Producer-director Stanley Kramer assembled a star-studded ensemble cast which included Spencer Tracy and Burt Lancaster. They “worked for nominal wages out of a desire to see the film made and for the opportunity to appear in it,” notes film historian George McManus. Actor William Shatner remembers that prior to the actual filming, “we understood the importance of the film we were making.” It was nominated for eleven Academy Awards, winning two. In 2011, Schell appeared at a 50th anniversary tribute to the film and his Oscar win, held in Los Angeles at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, where he spoke about his career and the film. Beginning in 1968 Schell began writing, producing, directing and acting in a number of his own films: Among those were The Castle (1968), a German film based on the novel by Franz Kafka, about a man trapped in a bureaucratic nightmare. Soon after he made Erste Liebe (First Love) (1970), based on a novel by Ivan Turgenev. The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Schell’s next film, The Pedestrian (1974), is about a German tycoon “haunted by his Nazi past”. In this film, notes one critic, “Schell probes the conscience and guilt in terms of the individual and of society, reaching to the universal heart of responsibility and moral inertia.” It was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar and was a “great and commercial success in Germany,” notes Roger Ebert. Schell then produced, directed and acted as a supporting character in End of the Game (1975), a German crime thriller starring Jon Voight and Jacqueline Bisset. A few years later he co-wrote and directed the Austrian film Tales from the Vienna Woods (1979). Drawing of Schell after he won an Oscar for Judgment at Nuremberg (1961). Artist: Nicholas Volpe During his career, as one of the few German-speaking actors working in English-language films, Schell was top billed in a number of Nazi-era themed films, including Counterpoint (1968), The Odessa File (1974), The Man in the Glass Booth (1975), A Bridge Too Far (1977), Cross of Iron (1977) and Julia (1977). For the latter film, directed by Fred Zinnemann, Schell was again nominated for an Oscar for his supporting role as an anti-Nazi activist. In a number of films Schell played the role of a Jewish character: as Otto Frank, Anne Frank’s father, in The Diary of Anne Frank (1980); as the modern Zionist father in The Chosen (1981); in 1996, he played an Auschwitz survivor in Through Roses, a German film, written and directed by Jrgen Flimm; and in Left Luggage (1998) he played the father of a Jewish family. In The Man in the Glass Booth (1975), adapted from the stage play by Robert Shaw, Schell played both a Nazi officer and a Jewish Holocaust survivor, in a character with a double identity. Roger Ebert describes the main character, Albert Goldman, as “mad, and immensely complicated, and he is hidden in a maze of identities so thick that no one knows for sure who he really is.” Schell, who at that period in his career saw himself primarily as a director, felt compelled to accept the part when it was offered to him: It’s just that once in a long while a role comes along that I simply can’t turn down. This was a role like that how could I say no to it? Schell’s acting in the film has been compared favorably to his other leading roles, with film historian Annette Insdorf writing, “Maximilian Schell is even more compelling as the quick-tempered, quicksilver Goldman than in his previous Holocaust-related roles, including Judgment at Nuremberg and The Condemned of Altona”. She gives a number of examples of Schell’s acting intensity, including the courtroom scenes, where Schell’s character, after supposedly being exposed as a German officer, “attacks Jewish meekness” in his defense, and “boasts that the Jews were sheep who didn’t believe what was happening.” The film eventually suggests that Schell’s character is in fact a Jew, but one whose sanity has been compromised by “survivor guilt.” Schell was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor and the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor for his performance. To avoid being typecast, Schell also played more diverse characters in numerous films throughout his career: he played a museum treasure thief in Topkapi (1964); a Venezuelan leader in Simn Bolvar (1969); a 19th-century ship captain in Krakatoa, East of Java (1969); a Captain Nemo-esque scientist/starship commander in the science fiction film, The Black Hole (1979); the Russian emperor in the television miniseries, Peter the Great (1986), opposite Laurence Olivier, Vanessa Redgrave and Trevor Howard, which won an Emmy Award; a comedy role with Marlon Brando in The Freshman (1990); Reese Witherspoon‘s surrogate grandfather in A Far Off Place; a treacherous Cardinal in John Carpenter’s Vampires (1998); as Frederick the Great in a TV film, Young Catherine (1991); as Vladimir Lenin in the TV series, Stalin (1992), for which he won the Golden Globe Award; a Russian KGB colonel in Candles in the Dark (1993); the Pharaoh in Abraham (1994); and Tea Leoni‘s father in the science fiction thriller, Deep Impact (1998). From the 1990s until late in his career, Schell appeared in many German-language made-for-TV films, such as the 2003 film Alles Glck dieser Erde (All the Luck in the World) opposite Uschi Glas and in the television miniseries The Return of the Dancing Master (2004), which was based on Henning Mankell‘s novel. In 2006 he appeared in the stage play of Arthur Miller‘s Resurrection Blues, directed by Robert Altman, which played in London at the Old Vic. In 2007, he played the role of Albert Einstein on the German television series Giganten (Giants), which enacted the lives of people important in German history. With his sister, actress Maria Schell, in 1959 Schell also served as a writer, producer and director for a variety of films, including the problematic documentary film Marlene (1984), with the unwilling participation of Marlene Dietrich. It was nominated for an Oscar, received the New York Film Critics Award and the German Film Award. Originally, Dietrich, then 83 years of age, had agreed to allow Schell to interview and film her in the privacy of her apartment. However, after he began filming, she changed her mind and refused to allow any actual video footage of her be shown. During a videotaped interview, Schell described the difficulties he had while making the film. Schell creatively showed only silhouettes of her along with old film clips during their interview soundtrack. According to one review, “the true originality of the movie is the way it pursues the clash of temperament between interviewer and star. . . . he draws her out, taunting her into a fascinating display of egotism, lying and contentiousness.” In 2002, Schell produced his most intimate film, My Sister Maria, a documentary about his sister, noted actress Maria Schell. In the film, he chronicles her life, career and eventual diminished capacity due to illness. The film, made three years before her death, shows her mental and physical frailty, leading to her withdrawing from the world. In 2002, upon the completion of the film, they both received Bambi Awards, and were honored for their lifetime achievements and in recognition of the film.

During the 1960s Schell had a three-year-long affair with Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari, former wife of the last Shah of Iran. He also was rumored to have been engaged to the first African American Supermodel Donyale Luna in the mid 1960s. In 1985 he met the Russian actress Natalya Andrejchenko, whom he married in June 1986; their daughter Nastassja was born in 1989. After 2002, separated from his wife (whom he divorced in 2005), Schell had a relationship with the Austrian art historian Elisabeth Michitsch. From 2008 he was romantically involved with German opera singer Iva Mihanovic; they eventually married on 20 August 2013. Schell was a semi-professional pianist for much of his life. He had a piano when he lived in Munich and said that he would play for hours at a time for his own pleasure and to help him relax: “I find I need to rest. An actor must have pauses in between work, to renew himself, to read, to walk, to chop wood.” Conductor Leonard Bernstein claimed that Schell was a “remarkably good pianist.” In 1982, on a program filmed for the U.S. television network PBS, before Bernstein conducted the Vienna Philharmonic playing Beethoven symphonies, Schell read from Beethoven’s letters to the audience. In 1983, he and Bernstein co-hosted an 11-part TV series, Bernstein/Beethoven, featuring nine live symphonies, along with discussions between Bernstein and Schell about Beethoven’s works. On other occasions, Schell worked with Italian conductor Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic, which included a performance in Chicago of Igor Stravinsky‘s Oedipus Rex, and another in Jerusalem, of Arnold Schoenberg‘s A Survivor from Warsaw. Schell also produced and directed a number of live operas, including Richard Wagner‘s Lohengrin for the Los Angeles Opera. He worked on the film project Beethoven’s Fidelio, with Plcido Domingo and Kent Nagano. Schell was a guest professor at the University of Southern California and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership in Chicago.

Schell died age 83 on 1 February 2014, in Innsbruck, Austria after a “sudden and serious illness”. The German television news service Tagesschau reported that he had been receiving treatment for pneumonia. His grave is in Preitenegg/Carinthia (Austria) where the family home was and where he and his sister lived until the end.

Overview

Early life

Career

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

Independent filmmaker

World War II themes

Character actor

Documentaries

Personal Life

Death

Filmography

Other Awards and Nominations