Overview

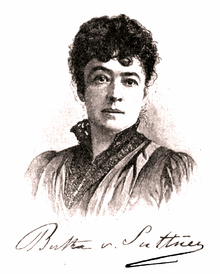

Bertha Felicitas Sophie Freifrau von Suttner (Baroness Bertha von Suttner, ne Countess Kinsky , Grfin Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau; 9 June 1843 – 21 June 1914) was an Austrian–Bohemian pacifist and novelist. In 1905 she became the second female Nobel laureate (after Marie Curie in 1903), the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and the first Austrian laureate.

Early life

Suttner was born on 9 June 1843 at Kinsk Palace in the Obecn dvr district of Prague. Her parents were the Austrian Lieutenant general (German: Feldmarschall-Leutnant) Franz de Paula Josef Graf Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau, recently deceased at the age of 75, and his wife Sophie Wilhelmine von Krner, who was fifty years his junior. Her father was a member of the Czech House of Kinsky via descent from Vilm Kinsk. Suttner’s mother came from a family that belonged to untitled nobility of significantly lower status, being the daughter of Joseph von Krner, a cavalry officer, and a distant relative of the poet Theodor Krner. For the rest of her life, Suttner faced exclusion from the Austrian high aristocracy due to her mixed descent; for instance only those with unblemished aristocratic pedigree back to their great-great-grandparents were eligible to be presented at court. She was additionally disadvantaged because her father, as a third son, had no great estates or other financial resources to be inherited. Suttner was baptised at the Church of Our Lady of the Snows, not a traditional choice for the aristocracy.

Soon after her birth, Suttner’s mother moved to live in Brno with her guardian Landgrave Friedrich Michael zu Frstenberg (1793-1866). Her older brother Arthur was sent to a military school, at the age of six, and subsequently had little contact with the family. In 1855 Suttner’s aunt Loffe and cousin Elvira joined the household. Elvira, whose father was a private tutor, was of a similar age to Suttner and interested in intellectual pursuits, introducing Suttner to literature and philosophy. Beyond her reading, Suttner gained proficiency in French, Italian and English as an adolescent, under the supervision of a succession of private tutors; she also became an accomplished amateur pianist and singer.

Suttner’s mother and aunt considered themselves to be clairvoyant and thus went to gamble at Wiesbaden in the summer of 1856, hoping to return with a fortune. Their losses were so heavy that they were forced to move to Vienna. During this trip Suttner received a proposal from Prince Philipp zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg which was declined due to her young age. The family returned to Wiesbaden in 1859; the second trip was similarly unsuccessful, and they had to relocate to a small property in Klosterneuburg. Shortly after this, Suttner wrote her first published work, the novella Endertrame im Monde, which appeared in Die Deutsche Frau. Continuing poor financial circumstances led Suttner to a brief engagement to the wealthy Gustav Heine von Geldern, thirty-one years her senior, whom she came to find unattractive and rejected; her memoirs record her disgusted response to the older man’s attempt to kiss her.

In 1864, the family spent the summer at Bad Homburg which was also a fashionable gambling destination among the aristocracy of the era. Suttner befriended the Georgian aristocrat Ekaterine Dadiani, Princess of Mingrelia, and met Tsar Alexander II. Seeking a career as an opera singer as an alternative to marrying into money, Suttner undertook an intensive course of lessons, working on her voice for over four hours a day. Despite tuition from the eminent Gilbert Duprez in Paris in 1867, and from Pauline Viardot in Baden-Baden in 1868, she never secured a professional engagement. She suffered from stage fright and was unable to project well in performance. In the summer of 1872 she was engaged to Prince Adolf zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein, who died at sea while travelling to America to escape his debts in October.

Tutor in the Suttner household, life in Georgia”]

Both Elvira and her guardian Friederich had died in 1866, and Suttner, now above the typical age of marriage, felt increasingly constrained by her mother’s eccentricity and the family’s poor financial circumstances. In 1873, she found employment as a tutor and companion to the four daughters of Karl von Suttner, aged between fifteen and twenty. The Suttner family lived in the Innere Stadt of Vienna three seasons of the year, and spent the summer at Schloss Harmannsdorf in Lower Austria. Suttner had an affectionate relationship with her four young students, who nicknamed her “Boulotte” due to her size, a name she would later adopt as a literary pseudonym in the form “B. Oulot”. She soon fell in love with the girls’ elder brother, Arthur Gundaccar, who was seven years her junior. They were engaged but unable to marry due to the Suttners’ disapproval. In 1876, with the encouragement of her employers, Suttner answered a newspaper advertisement which led to her briefly becoming secretary and housekeeper to Alfred Nobel in Paris. In the few weeks of her employment Suttner and Nobel developed a friendship, and Nobel may have made romantic overtures. However, Suttner remained committed to Arthur and returned shortly to Vienna to marry him in secrecy, in the church of St. Aegyd in Gumpendorf.

The newlywed couple eloped to Mingrelia, where Suttner hoped to make use of her connection to the former ruling House of Dadiani. On their arrival they were entertained by Prince Niko. The couple settled in Kutaisi, where they found work teaching languages and music to the children of the local aristocracy. However, they experienced considerable hardship despite their social connections, living in a simple three-roomed wooden house. Their situation worsened in 1877 on the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War, although Arthur worked as a reporter on the conflict for the Neue Freie Presse. Suttner also wrote frequently for the Austrian press in this period, and worked on her early novels, including in Es Lwos a romanticized account of her life with Arthur. In the aftermath of the war, Arthur attempted to set up a timber business, but it was unsuccessful.

Arthur and Bertha von Suttner

Arthur and Suttner were largely socially isolated in Georgia; their poverty restricted their engagement with high society, and neither ever became fluent speakers of Mingrelian or Georgian. To support themselves, both began writing as a career. While Arthur’s writing during this period is dominated by local themes, Suttner’s was not similarly influenced by Georgian culture.

In August 1882 Ekaterine Dadiani died. Soon afterwards, the couple decided to move to Tbilisi. Here Arthur took whatever work he could, in accounting, construction and wallpaper design, while Suttner largely concentrated on her writing. She became a correspondent of Michael Georg Conrad, eventually contributing an article to the 1885 edition of his publication Die Gesellschaft. The piece, entitled “Truth and Lies”, is a polemic in favour of the naturalism of mile Zola. Her first significant political work, Inventarium einere Seele (“Inventory of the Soul”) was published in Leipzig in 1883. In this work, Suttner takes a pro-disarmament, progressive stance, arguing for the inevitability of world peace due to technological advancement; a possibility also considered by her friend Nobel due to the increasingly deterrent effect of more powerful weapons.

In 1884 Suttner’s mother died, leaving the couple with further debts. Arthur had befriended a Georgian journalist in Tbilisi, M, and the couple agreed to collaborate with him on a translation of the Georgian epic The Knight in the Panther Skin. Suttner was to improve M.’s literal translation of the Georgian to French, and Arthur to translate the French to German. This method proved arduous, and they worked for few hours each day due to the distraction of the Mingrelian countryside around M.’s home. Arthur published several articles on the work in the Georgian press, and Mihly Zichy prepared some illustrations for the publication, but M. failed to make the expected payment, and after the Bulgarian Crisis began in 1885 the couple felt increasingly unsafe in Georgian society, which was becoming more hostile to Austrians due to Russian influence. They finally reconciled with Arthur’s family and in May 1885 could return to Austria, where the couple lived at Harmannsdorf Castle in Lower Austria.

Bertha found refuge in her marriage with Arthur, of which she remarked that “the third field of my feelings and moods lay within our married happiness. In this was my peculiarly inalienable home, my refuge for all possible conditions of life, ….and so the leaves of my diary are full not only of political domestic records of all kinds, but also of memoranda of our gay little jokes, our confidential enjoyable walks, our uplifting reading, our hours of music together, and our evening games of chess. To us personally nothing could happen. We had each other, – that was everything.”

Peace activism

After their return to Austria, Suttner continued her journalism and concentrated on peace and conflict studies, corresponding with the French philosopher Ernest Renan and influenced by the International Arbitration and Peace Association founded by Hodgson Pratt in 1880.

In 1889 Suttner became a leading figure in the peace movement with the publication of her pacifist novel, Die Waffen nieder! (Down with Weapons!), which made her one of the leading figures of the Austrian peace movement. The book was published in 37 editions and translated into 12 languages (titled Lay Down Your Arms! in English). She witnessed the foundation of the Inter-Parliamentary Union and called for the establishment of the Austrian Gesellschaft der Friedensfreunde pacifist organization in an 1891 Neue Freie Presse editorial. Suttner became chairwoman and also founded the German Peace Society the next year. She became known internationally as the editor of the international pacifist journal Die Waffen nieder!, named after her book, from 1892 to 1899. In 1897 she presented Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria with a list of signatures urging the establishment of an International Court of Justice and took part in the First Hague Convention in 1899 with the help of Theodor Herzl, who paid for her trip.

Upon her husband’s death in 1902, Suttner had to sell Harmannsdorf Castle and moved back to Vienna. In 1904 she addressed the International Congress of Women in Berlin and for seven months travelled around the United States, attending a universal peace congress in Boston and meeting President Theodore Roosevelt.

Though her personal contact with Alfred Nobel had been brief, she corresponded with him until his death in 1896, and it is believed that she was a major influence on his decision to include a peace prize among those prizes provided in his will, which she was awarded in the fifth term on 10 December 1905. The presentation took place on 18 April 1906 in Kristiania.

Imaginative drawing by Marguerite Martyn and a photo of Bertha von Suttner, 1912, with a victorious Suttner holding a scroll labeled “International Peace Treaty / England / France / America.” In the corner cowers a representation of a defeated warrior labeled “WAR.” A broken sword and shield is on the ground. A tangle of broken warships is at the left side. At top are newspaper headlines from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of October 20, 1912.

In 1907 Suttner attended the Second Hague Peace Conference, which however mainly pertained to the law of war. In the run-up to World War I, she continued to campaign against international armament. In 1911 she became a member of the advisory council of the Carnegie Peace Foundation. In the last months of her life, while suffering from cancer, she helped organize the next Peace Conference, intended to take place in September 1914. However, the conference never took place, as she died of cancer on 21 June 1914, and a few weeks later Franz Ferdinand was killed, triggering World War I.

Suttner’s pacifism was influenced by the writings of Immanuel Kant, Henry Thomas Buckle, Herbert Spencer, Charles Darwin and Leo Tolstoy (Tolstoy praised Die Waffen nieder!) conceiving peace as a natural state impaired by the human aberrances of war and militarism. As a result, she argued that a right to peace could be demanded under international law and was necessary in the context of an evolutionary Darwinist conception of history. Suttner was a respected journalist, with one historian describing her as “a most perceptive and adept political commentator”.

Writing

As a career writer, von Suttner often had to write novels and novellas that she did not believe in or really want to write, to support herself. However, even in those novels there are traces of her political ideals; often, the romantic heroes would fall in love upon realizing they were both fighting for the same ideals, usually peace and tolerance.

To promote her writing career and ideals, she used her connections in aristocracy and friendships with wealthy individuals, such as Alfred Nobel, to gain access to international heads of state, and also to gain popularity for her writing. To increase the financial success of her writing, she used a male pseudonym early in her career. In addition, Suttner often worked as a journalist to publicise her message or promote her own books, events, and causes.

As Tolstoy noted and others have since agreed, there is a strong similarity between Suttner and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Both Beecher Stowe and von Suttner “were neither simply writers of popular entertainment nor authors of tendentious propaganda…. used entertainment for idealistic purposes.” For Suttner, peace and acceptance of all individuals and all peoples was the greatest ideal and theme.

Religion

There are two main issues with religion that Bertha von Suttner often wrote about. She had a disdain for the spectacle and pomp of some religious practices. In a scene in Lay Down Your Arms she highlighted the odd theatricality of some religious practices. In the scene, the emperor and empress are washing the feet of normal citizens to show they are as humble as Jesus, but they invite everyone to witness their show of humility and enter the hall in a dramatic fashion. The protagonist Martha remarks that it was “indeed a sham washing.”

This type of religious thinking also leads to segregation and fighting based on religious differences, which Bertha and Arthur von Suttner refused to accept. As a devout Christian, Arthur founded the League Against Anti-Semitism in response to the pogroms in Eastern Europe and the growing antisemitism across Europe. The Suttner family called for acceptance of all people and all faiths, with Von Suttner writing in her memoirs that “religion was neighborly love, not neighborly hatred. Any kind of hatred, against other nations or against other creeds, detracted from the humaneness of humanity.”

Gender

Bertha von Suttner is often considered a leader in the women’s liberation movement. In Lay Down Your Arms, the protagonist Martha often clashes with her father on this issue. Martha does not want her son to play with toy soldiers and be indoctrinated to the masculine ideas of war. Martha’s father attempts to put Martha back in the female gendered box by suggesting that the son will not need to ask for approval from a woman, and also states that Martha should marry again because women her age should not be alone.

This was not simply because she insisted that women are equal to men, but that she was able to tease out how sexism affects both men and women. Like Martha being placed in a female structured gender box, the character of Tilling is also placed in the male stereotyped box and affected by that. The character even discusses it, saying, “we men have to repress the instinct of self-preservation. Soldiers have also to repress the compassion, the sympathy for the gigantic trouble which invades both friend and foe; for next to cowardice, what is most disgraceful to us is all sentimentality, all that is emotional.”

Legacy

|

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Although Bertha von Suttner was not financially successful during her lifetime, her work has remained influential for those involved in the peace movement.

She has also been commemorated on several coins and stamps:

- She was selected as a main motif for a high value collectors’ coin: the 2008 Europe Taler, which featured important people in the history of Europe. Also depicted in the coin are Martin Luther, Antonio Vivaldi, and James Watt.

- She is depicted on Germany’s 2005 10 euro coin.

- She is depicted on the Austrian 2 euro coin, and was pictured on the old Austrian 1000 schilling bank note.

- She was commemorated on a 1965 Austrian postage stamp and a 2005 German postage stamp.

On film

- Die Waffen nieder, by Holger Madsen and Carl Theodor Dreyer. Released by Nordisk Films Kompagni in 1914.

- No Greater Love (German: Herz der Welt), a 1952 film has Bertha as the main character.

TV

- Eine Liebe fr den Frieden – Bertha von Suttner und Alfred Nobel (A Love for Peace – Bertha von Suttner and Alfred Nobel), TV biopic, ORF/Degeto/BR 2014, after the play Mr. & Mrs. Nobel by Esther Vilar.

Works in English translation

- Memoirs of Bertha von Suttner; The Records of an Eventful Life, Pub. for the International School of Peace, Ginn and company, 1910.

- When Thoughts Will Soar; A Romance of the Immediate Future, by Baroness Bertha von Suttner … tr. by Nathan Haskell Dole. Boston, New York, Houghton Mifflin company, 1914.

- Lay Down Your Arms; The Autobiography of Martha von Tilling, by Bertha von Suttner. Authorised translation by T. Holmes, rev. by the author. 2d ed. New York, Longmans, Green and Co., 1906.