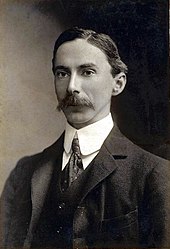

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell ( 18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher,

logician, mathematician, historian, writer, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate. At various points in his life, Russell considered himself a liberal, a socialist and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had “never been any of these things, in any profound sense”. Russell was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the United Kingdom. Russell was a prominent anti-war activist and he championed anti-imperialism. Occasionally, he advocated preventive nuclear war, before the opportunity provided by the atomic monopoly had passed and “welcomed with enthusiasm” world government. He went to prison for his pacifism during World War I. Later, Russell concluded that war against Adolf Hitler‘s Nazi Germany was a necessary “lesser of two evils” and criticized Stalinist totalitarianism, attacked the involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War and was an outspoken proponent of nuclear disarmament. In 1950, Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought“.

Bertrand Russell was born on 18 May 1872 at Ravenscroft, Trellech, Monmouthshire, into an influential and liberal family of the British aristocracy. His parents, Viscount and Viscountess Amberley, were radical for their times. Lord Amberley consented to his wife’s affair with their children’s tutor, the biologist Douglas Spalding. Both were early advocates of birth control at a time when this was considered scandalous. Lord Amberley was an atheist and his atheism was evident when he asked the philosopher John Stuart Mill to act as Russell’s secular godfather. Mill died the year after Russell’s birth, but his writings had a great effect on Russell’s life. Lady Amberley was the daughter of Lord and Lady Stanley of Alderley. Russell often feared the ridicule of his maternal grandmother, one of the campaigners for education of women. Russell had two siblings: brother Frank (nearly seven years older than Bertrand), and sister Rachel (four years older). In June 1874 Russell’s mother died of diphtheria, followed shortly by Rachel’s death. In January 1876, his father died of bronchitis following a long period of depression. Frank and Bertrand were placed in the care of their staunchly Victorian paternal grandparents, who lived at Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park. His grandfather, former Prime Minister Earl Russell, died in 1878, and was remembered by Russell as a kindly old man in a wheelchair. His grandmother, the Countess Russell (ne Lady Frances Elliot), was the dominant family figure for the rest of Russell’s childhood and youth. Russell’s adolescence was very lonely, and he often contemplated suicide. He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests were in religion and mathematics, and that only his wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide. He was educated at home by a series of tutors. When Russell was eleven years old, his brother Frank introduced him to the work of Euclid, which transformed his life. Russell won a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and commenced his studies there in 1890, taking as coach Robert Rumsey Webb. He became acquainted with the younger George Edward Moore and came under the influence of Alfred North Whitehead, who recommended him to the Cambridge Apostles. He quickly distinguished himself in mathematics and philosophy, graduating as seventh Wrangler in the former in 1893 and becoming a Fellow in the latter in 1895. Russell first met the American QuakerAlys Pearsall Smith when he was 17 years old. He became a friend of the Pearsall Smith family – they knew him primarily as “Lord John’s grandson” and enjoyed showing him off. He traveled with them to the continent; it was in their company that Russell visited the Paris Exhibition of 1889 and was able to climb the Eiffel Tower soon after it was completed. He soon fell in love with the puritanical, high-minded Alys, who was a graduate of Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, and, contrary to his grandmother’s wishes, married her on 13 December 1894. Their marriage began to fall apart in 1901 when it occurred to Russell, while he was cycling, that he no longer loved her. She asked him if he loved her and he replied that he did not. Russell also disliked Alys’s mother, finding her controlling and cruel. It was to be a hollow shell of a marriage and they finally divorced in 1921, after a lengthy period of separation. During this period, Russell had passionate (and often simultaneous) affairs with a number of women, including Lady Ottoline Morrell and the actress Lady Constance Malleson. Some have suggested that at this point he had an affair with Vivienne Haigh-Wood, the English governess and writer, and first wife of T. S. Eliot. Russell began his published work in 1896 with German Social Democracy, a study in politics that was an early indication of a lifelong interest in political and social theory. In 1896 he taught German social democracy at the London School of Economics. He was a member of the Coefficients dining club of social reformers set up in 1902 by the Fabian campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb. In 1910 he became a University of Cambridge lecturer at Trinity College where he studied. He was considered for a Fellowship, which would give him a vote in the college government and protect him from being fired for his opinions, but was passed over because he was “anti-clerical”, essentially because he was agnostic. He was approached by the Austrian engineering student Ludwig Wittgenstein, who became his PhD student. Russell viewed Wittgenstein as a genius and a successor who would continue his work on logic. He spent hours dealing with Wittgenstein’s various phobias and his frequent bouts of despair. This was often a drain on Russell’s energy, but Russell continued to be fascinated by him and encouraged his academic development, including the publication of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1922. Russell delivered his lectures on Logical Atomism, his version of these ideas, in 1918, before the end of World War I. Wittgenstein was, at that time, serving in the Austrian Army and subsequently spent nine months in an Italian prisoner of war camp at the end of the conflict. During World War I, Russell was one of the few people to engage in active pacifist activities and in 1916, because of his lack of a Fellowship, he was dismissed from Trinity College following his conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914. He later described this as an illegitimate means the state used to violate freedom of expression, in Free Thought and Official Propaganda. Russell played a significant part in the Leeds Convention in June 1917, a historic event which saw well over a thousand “anti-war socialists” gather; many being delegates from the Independent Labour Party and the Socialist Party, united in their pacifist beliefs and advocating a peace settlement. The international press reported that Russell appeared with a number of Labour MPs, including Ramsay MacDonald and Philip Snowden, as well as former Liberal MP and anti-conscription campaigner, Professor Arnold Lupton. After the event, Russell told Lady Ottoline Morrell that, “to my surprise, when I got up to speak, I was given the greatest ovation that was possible to give anybody”. A later conviction for publicly lecturing against inviting the US to enter the war on the United Kingdom’s side resulted in six months’ imprisonment in Brixton prison in 1918. He later said of his imprisonment: In 1941, G. H. Hardy wrote a 61-page pamphlet titled Bertrand Russell and Trinity – published later as a book by Cambridge University Press with a foreword by C. D. Broad – in which he gave an authoritative account about Russell’s 1916 dismissal from Trinity College, explaining that a reconciliation between the college and Russell had later taken place and gave details about Russell’s personal life. Hardy writes that Russell’s dismissal had created a scandal since the vast majority of the Fellows of the College opposed the decision. The ensuing pressure from the Fellows induced the Council to reinstate Russell. In January 1920, it was announced that Russell had accepted the reinstatement offer from Trinity and would begin lecturing from October. In July 1920, Russell applied for a one year leave of absence; this was approved. He spent the year giving lectures in China and Japan. In January 1921, it was announced by Trinity that Russell had resigned and his resignation had been accepted. This resignation, Hardy explains, was completely voluntary and was not the result of another altercation. The reason for the resignation, according to Hardy, was that Russell was going through a tumultuous time in his personal life with a divorce and subsequent remarriage. Russell contemplated asking Trinity for another one-year leave of absence but decided against it, since this would have been an “unusual application” and the situation had the potential to snowball into another controversy. Although Russell did the right thing, in Hardy’s opinion, the reputation of the College suffered due to Russell’s resignation since the world of learning knew about Russell’s altercation with Trinity but not that the rift had healed. In 1925, Russell was asked by the Council of Trinity College to give the Tarner Lectures on the Philosophy of the Sciences; these would later be the basis for one of Russell’s best received books according to Hardy: The Analysis of Matter, published in 1927. In the preface to this pamphlet, Hardy wrote: I wish to make it plain that Russell himself is not responsible, directly or indirectly, for the writing of the pamphlet … I wrote it without his knowledge and, when I sent him the typescript and asked for his permission to print it, I suggested that, unless it contained misstatement of fact, he should make no comment on it. He agreed to this … no word has been changed as the result of any suggestion from him. In August 1920, Russell travelled to Russia as part of an official delegation Russell’s lover Dora Black, a British author, feminist and socialist campaigner, visited Russia independently at the same time; in contrast to his reaction, she was enthusiastic about the revolution. From 1922 to 1927 the Russells divided their time between London and Cornwall, spending summers in Porthcurno. In the 1922 and 1923 general elections Russell stood as a Labour Party candidate in the Chelsea constituency, but only on the basis that he knew he was extremely unlikely to be elected in such a safe Conservative seat, and he was not on either occasion. Together with Dora, Russell founded the experimental Beacon Hill School in 1927. The school was run from a succession of different locations, including its original premises at the Russells’ residence, Telegraph House, near Harting, West Sussex. On 8 July 1930 Dora gave birth to her third child Harriet Ruth. After he left the school in 1932, Dora continued it until 1943. Upon the death of his elder brother Frank, in 1931, Russell became the 3rd Earl Russell. Russell’s marriage to Dora grew increasingly tenuous, and it reached a breaking point over her having two children with an American journalist, Griffin Barry. They separated in 1932 and finally divorced. On 18 January 1936, Russell married his third wife, an Oxford undergraduate named Patricia (“Peter”) Spence, who had been his children’s governess since 1930. Russell and Peter had one son, Conrad Sebastian Robert Russell, 5th Earl Russell, who became a prominent historian and one of the leading figures in the Liberal Democrat party. Russell opposed rearmament against Nazi Germany. In 1937 he wrote in a personal letter: “If the Germans succeed in sending an invading army to England we should do best to treat them as visitors, give them quarters and invite the commander and chief to dine with the prime minister.” In 1940, he changed his view that avoiding a full-scale world war was more important than defeating Hitler. He concluded that Adolf Hitler taking over all of Europe would be a permanent threat to democracy. In 1943, he adopted a stance toward large-scale warfare: “War was always a great evil, but in some particularly extreme circumstances, it may be the lesser of two evils.”Overview

In the early 20th century, Russell led the British “revolt against idealism“. He is considered one of the founders of analytic philosophy along with his predecessor Gottlob Frege, colleague G. E. Moore and protg Ludwig Wittgenstein. He is widely held to be one of the 20th century’s premier logicians. With A. N. Whitehead he wrote Principia Mathematica, an attempt to create a logical basis for mathematics. His philosophical essay “On Denoting” has been considered a “paradigm of philosophy”. His work has had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science (see type theory and type system) and philosophy, especially the philosophy of language, epistemology and metaphysics.Biography

Early life and background

His paternal grandfather, the Earl Russell, had been asked twice by Queen Victoria to form a government, serving her as Prime Minister in the 1840s and 1860s. The Russells had been prominent in England for several centuries before this, coming to power and the peerage with the rise of the Tudor dynasty (see: Duke of Bedford). They established themselves as one of the leading British Whig families, and participated in every great political event from the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536-1540 to the Glorious Revolution in 1688-1689 and the Great Reform Act in 1832.Childhood and adolescence

The countess was from a Scottish Presbyterian family, and successfully petitioned the Court of Chancery to set aside a provision in Amberley’s will requiring the children to be raised as agnostics. Despite her religious conservatism, she held progressive views in other areas (accepting Darwinism and supporting Irish Home Rule), and her influence on Bertrand Russell’s outlook on social justice and standing up for principle remained with him throughout his life. (One could challenge the view that Bertrand stood up for his principles, based on his own well-known quotation: “I would never die for my beliefs because I might be wrong”.) Her favourite Bible verse, ‘Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil’ (Exodus 23:2), became his motto. The atmosphere at Pembroke Lodge was one of frequent prayer, emotional repression, and formality; Frank reacted to this with open rebellion, but the young Bertrand learned to hide his feelings.

During these formative years he also discovered the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. In his autobiography, he writes: “I spent all my spare time reading him, and learning him by heart, knowing no one to whom I could speak of what I thought or felt, I used to reflect how wonderful it would have been to know Shelley, and to wonder whether I should meet any live human being with whom I should feel so much sympathy”. Russell claimed that beginning at age 15, he spent considerable time thinking about the validity of Christian religious dogma, which he found very unconvincing. At this age, he came to the conclusion that there is no free will and, two years later, that there is no life after death. Finally, at the age of 18, after reading Mill’s “Autobiography”, he abandoned the “First Cause” argument and became an atheist.University and first marriage

Early career

He now started an intensive study of the foundations of mathematics at Trinity. In 1898 he wrote An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry which discussed the Cayley-Klein metrics used for non-Euclidean geometry. He attended the International Congress of Philosophy in Paris in 1900 where he met Giuseppe Peano and Alessandro Padoa. The Italians had responded to Georg Cantor, making a science of set theory; they gave Russell their literature including the Formulario mathematico. Russell was impressed by the precision of Peano’s arguments at the Congress, read the literature upon returning to England, and came upon Russell’s paradox. In 1903 he published The Principles of Mathematics, a work on foundations of mathematics. It advanced a thesis of logicism, that mathematics and logic are one and the same.

At the age of 29, in February 1901, Russell underwent what he called a “sort of mystic illumination”, after witnessing Whitehead‘s wife’s acute suffering in an angina attack. “I found myself filled with semi-mystical feelings about beauty … and with a desire almost as profound as that of the Buddha to find some philosophy which should make human life endurable”, Russell would later recall. “At the end of those five minutes, I had become a completely different person.”

In 1905 he wrote the essay “On Denoting“, which was published in the philosophical journal Mind. Russell was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1908. The three-volume Principia Mathematica, written with Whitehead, was published between 1910 and 1913. This, along with the earlier The Principles of Mathematics, soon made Russell world-famous in his field.First World War

The Trinity incident resulted in Russell being fined 100, which he refused to pay in hope that he would be sent to prison, but his books were sold at auction to raise the money. The books were bought by friends; he later treasured his copy of the King James Bible that was stamped “Confiscated by Cambridge Police”.

I found prison in many ways quite agreeable. I had no engagements, no difficult decisions to make, no fear of callers, no interruptions to my work. I read enormously; I wrote a book, “Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy”… and began the work for “Analysis of Mind”

Russell was reinstated to Trinity in 1919, resigned in 1920, was Tarner Lecturer 1926 and became a Fellow again in 1944 until 1949.

In 1924, Bertrand again gained press attention when attending a “banquet” in the House of Commons with well-known campaigners, including Arnold Lupton, who had been a Member of Parliament and had also endured imprisonment for “passive resistance to military or naval service”.G. H. Hardy on the Trinity controversy and Russell’s personal life

Between the Wars

sent by the British government to investigate the effects of the Russian

Revolution. He wrote a four-part series of articles, titled “Soviet Russia1920”, for the US magazine The Nation. He met Vladimir Lenin and had an hour-long conversation with him. In his autobiography, he mentions that he found Lenin disappointing, sensing an “impish cruelty” in him and comparing him to “an opinionated professor”. He cruised down the Volga on a steamship. His experiences destroyed his previous tentative support for the revolution. He wrote a book The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism about his experiences on this trip, taken with a group of 24 others from the UK, all of whom came home thinking well of the rgime, despite Russell’s attempts to change their minds. For example, he told them that he heard shots fired in the middle of the night and was sure these were clandestine executions, but the others maintained that it was only cars backfiring.

The following autumn Russell, accompanied by Dora, visited Peking (as it was then known in the West) to lecture on philosophy for a year. He went with optimism and hope, seeing China as then being on a new path. Other scholars present in China at the time included John Dewey and Rabindranath Tagore, the Indian Nobel-laureate poet. Before leaving China, Russell became gravely ill with pneumonia, and incorrect reports of his death were published in the Japanese press. When the couple visited Japan on their return journey, Dora took on the role of spurning the local press by handing out notices reading “Mr. Bertrand Russell, having died according to the Japanese press, is unable to give interviews to Japanese journalists”. Apparently they found this harsh and reacted resentfully.

Dora was six months pregnant when the couple returned to England on 26 August 1921. Russell arranged a hasty divorce from Alys, marrying Dora six days after the divorce was finalised, on 27 September 1921. Russell’s children with Dora were John Conrad Russell, 4th Earl Russell, born on 16 November 1921, and Katharine Jane Russell (now Lady Katharine Tait), born on 29 December 1923. Russell supported his family during this time by writing popular books explaining matters of physics, ethics, and education to the layman.

On a tour through the US in 1927 Russell met Barry Fox (later Barry Stevens) who became a well-known Gestalt therapist and writer in later years. Russell and Fox developed an intensive relationship. In Fox’s words: “… for three years we were very close.” Fox sent her daughter Judith to Beacon Hill School for some time. From 1927 to 1932 Russell wrote 34 letters to Fox.

Russell returned to the London School of Economics to lecture on the science of power in 1937.

During the 1930s, Russell became a close friend and collaborator of V. K. Krishna Menon, then secretary of the India League, the foremost lobby in the United Kingdom for Indian self-rule.Second World War

Before World War II, Russell taught at the University of Chicago, later moving on to Los Angeles to lecture at the UCLA Department of Philosophy. He was appointed professor at the City College of New York (CCNY) in 1940, but after a public outcry the appointment was annulled by a court judgment that pronounced him “morally unfit” to teach at the college due to his opinions, especially those relating to sexual morality, detailed in Marriage and Morals (1929). The matter was however taken to the New York Supreme Court by Jean Kay who was afraid that her daughter would be harmed by the appointment, though her daughter was not a student at CCNY. Many intellectuals, led by John Dewey, protested at his treatment.Albert Einstein‘s oft-quoted aphorism that “great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds” originated in his open letter, dated 19 March 1940, to Morris Raphael Cohen, a professor emeritus at CCNY, supporting Russell’s appointment. Dewey and Horace M. Kallen edited a collection of articles on the CCNY affair in The Bertrand Russell Case. Russell soon joined the Barnes Foundation, lecturing to a varied audience on the history of philosophy; these lectures formed the basis of A History of Western Philosophy. His relationship with the eccentric Albert C. Barnes soon soured, and he returned to the UK in 1944 to rejoin the faculty of Trinity College.