Overview of life

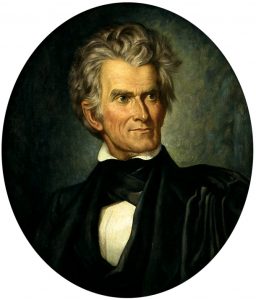

John Caldwell Calhoun (March 18, 1782 – March 31, 1850) was a leading American politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent of a strong national government and protective tariffs. After 1830, his views evolved and he became a greater proponent of states’ rights, limited government, nullification and free trade; as he saw these means as the only way to preserve the Union. He is best known for his intense and original defense of slavery as something positive, his distrust of majoritarianism, and for pointing the South toward secession from the Union.

Devoted to liberty in principle and fearful of corruption, Calhoun built his reputation as a political theorist by his redefinition of republicanism to include approval of slavery and minority rights—with the Southern States the minority in question. To protect minority rights against majority rule, he called for a “concurrent majority” whereby the minority could sometimes block offensive proposals that a State felt infringed on their sovereign power. Always distrustful of democracy, he minimized the role of the Second Party System in South Carolina. Calhoun’s defense of slavery became defunct, but his concept of concurrent majority, whereby a minority has the right to object to or even veto hostile legislation directed against it, has been cited by other advocates of the rights of minorities. Calhoun asserted that Southern whites, outnumbered in the United States by voters of the more densely-populated Northern states, were one such minority deserving special protection in the legislature. Calhoun also saw the increasing population disparity to be the result of corrupt northern politics.

Calhoun held major political offices, serving terms in the United States House of Representatives, United States Senate and as Vice President of the United States, as well as secretary of war and state. He usually affiliated with the Democrats, but flirted with the Whig Party and considered running for the presidency in 1824 and 1844. As a “war hawk”, he agitated in Congress for the War of 1812 to defend American honor against Britain. Near the end of the war, he successfully delayed a vote on US Treasury notes being issued, arguing that the bill would not pass if the war were to end in the near future; the day of the vote, Congress received word from New York that the war was over. As Secretary of War under President James Monroe, he reorganized and modernized the War Department, building powerful permanent bureaucracies that ran the department, as opposed to patronage appointees and did so while trimming the requested funding each year.

Calhoun died 11 years before the start of the American Civil War, but he was an inspiration to the secessionists of 1860–61. Nicknamed the “cast-iron man” for his ideological rigidity as well as for his determination to defend the causes he believed in, Calhoun supported states’ rights and nullification, under which states could declare null and void federal laws which they viewed as unconstitutional. He was an outspoken proponent of the institution of slavery, which he defended as a “positive good” rather than as a “necessary evil”. His rhetorical defense of slavery was partially responsible for escalating Southern threats of secession in the face of mounting abolitionist sentiment in the North.

Calhoun was one of the “Great Triumvirate” or the “Immortal Trio” of Congressional leaders, along with his Congressional colleagues Daniel Webster and Henry Clay. In 1957, a Senate Committee selected Calhoun as one of the five greatest U.S. Senators, along with Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Robert La Follette, and Robert Taft. Calhoun “was a public intellectual of the highest order…and a uniquely gifted American politician.”

Origin And Early Life

Origins and Early Life

Calhoun was born in 1782, the fourth child of Patrick Calhoun and his wife Martha Caldwell in Abbeville District, SC. His father had joined the Irish immigration from County Donegal to the backcountry of South Carolina.

When his father became ill, 17-year-old John Calhoun quit school to work on the family farm. With his brothers’ financial support, he later returned to his studies, earning a degree from Yale College, Phi Beta Kappa, in 1804. After studying law at the Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, he was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1807.

Marriage and Family

In January 1811, Calhoun married Floride Bonneau Colhoun, a first cousin once removed. The couple had 10 children over 18 years; three died in infancy: 1. Andrew Pickens Calhoun (1811–1865); 2. Floride Pure Calhoun (1814–1815); 3. Jane Calhoun (1816–1816); 4. Anna Maria Calhoun (1817–1875); 5. Elizabeth Calhoun (1819–1820); 6. Patrick Calhoun (1821–1858); 7. John Caldwell Calhoun, Jr. (1823–1855); 8. Martha Cornelia Calhoun (1824–1857); 9. James Edward Calhoun (1826–1861); and 10. William Lowndes Calhoun (1829–1858). His fourth child, Anna Maria, married Thomas Green Clemson, founder of Clemson University in South Carolina. During her husband’s second term as Vice President, Floride Calhoun was a central figure in the Petticoat affair. She was an active Episcopalian and Calhoun often accompanied her to church. However he was a charter member of All Souls Unitarian Church in Washington, D.C., in 1821 signing his name right next to John Quincy Adams and remaining a member for all his life. He rarely mentioned religion; a Presbyterian in his early life, historians believe he was closest to the informal Unitarianism typified by Thomas Jefferson. In Clyde Wilson’s collection of Calhoun’s papers, Wilson believes his religion is known to himself alone, although he loved to discuss religion. Calhoun’s closest quote about religion would be; “Do our best, our duty for our country, and leave the rest to Providence”- in a letter to Anna Maria. In John C. Calhoun: American Portrait, Margaret Coit shows how he was raised Calvinist, went into Unitarianism for a bit, but for most of his life was caught in between the two. Before he died, he was touched by the Great Awakening in the South, the book states.

“

Intensely serious and severe, he could never write a love poem, though he often tried, because every line began with “whereas”.

”

— Historian Merrill Peterson

War Hawk

Calhoun was “a high-strung man of ultra intellectual cast,”, and unlike Henry Clay or Andrew Jackson, he was not noted for charisma or charm (except when dealing with women and children). But he was a brilliant intellectual and orator and strong organizer. Historian Russell Kirk says “That zeal which flared like Greek fire in Randolph burned in Calhoun, too; but it was contained in the Cast-iron Man as in a furnace, and Calhoun’s passion glowed out only through his eyes. No man was more stately, more reserved.”

With a base among the Irish (or Scotch Irish), Calhoun won his first election to Congress in 1810. he immediately became a leader of the “War Hawks,” along with Speaker Henry Clay and South Carolina congressmen William Lowndes and Langdon Cheves. They disregarded European complexities in the wars between Napoleon and Britain, and brushed aside the vehement objections of New Englanders; they demanded war against Britain to preserve American honor and republican values. Clay made Calhoun the acting chairman of the powerful committee on foreign affairs. On June 3, 1812, Calhoun’s committee called for a declaration of war in ringing phrases. The episode spread Calhoun’s fame nationwide. War—the War of 1812—was declared, but it went very badly for the poorly organized Americans, whose ports were immediately blockaded by the British Royal Navy. Several attempted invasions of Canada were fiascos, but the U.S. did seize control of western Canada and broke the power of hostile Indians in battles in Canada and Alabama.

Calhoun labored to raise troops, to provide funds, to speed logistics, to improve the currency, and to regulate commerce to aid the war effort. Disasters on the battlefield made him double his legislative efforts to overcome the obstructionism of John Randolph of Roanoke and Daniel Webster and other opponents of the war. With Napoleon apparently gone, and the British invasion of New York defeated, British and American diplomats (Clay and John Quincy Adams among the American delegation) signed the Treaty of Ghent on Christmas Eve, 1814. Before the treaty reached the Senate for ratification, and even before news of its signing reached New Orleans, a massive British invasion force was utterly defeated at the Battle of New Orleans, making a national hero out of General Andrew Jackson. The mismanagement of the Army during the war distressed Calhoun, and he resolved to strengthen the War Department so it would never fail again.

Nationalist

After the war, Calhoun and Clay sponsored a Bonus Bill for public works. With the goal of building a strong nation that could fight future wars, Calhoun aggressively pushed for protective tariffs (to build up industry), a national bank, internal improvements (such as canals and ports), and other nationalist policies that he later repudiated because the ends had been accomplished. His repudiation of the national bank was tempered, as he suggested a winding down period to avoid economic shock.

John Quincy Adams concluded in 1821 that: “Calhoun is a man of fair and candid mind, of honorable principles, of clear and quick understanding, of cool self-possession, of enlarged philosophical views, and of ardent patriotism. He is above all sectional and factious prejudices more than any other statesman of this Union with whom I have ever acted.” Historian Charles Wiltse agrees, noting, “Though he is known today primarily for his sectionalism, Calhoun was the last of the great political leaders of his time to take a sectional position—later than Daniel Webster, later than Henry Clay, later than Adams himself.”

An observer commented that Calhoun was “the most elegant speaker that sits in the House… His gestures are easy and graceful, his manner forcible, and language elegant; but above all, he confines himself closely to the subject, which he always understands, and enlightens everyone within hearing; having said all that a statesman should say, he is done.” His talent for public speaking required systematic self-discipline and practice. A later critic noted the sharp contrast between his hesitant conversations and his fluent speaking styles, adding that Calhoun “had so carefully cultivated his naturally poor voice as to make his utterance clear, full, and distinct in speaking and while not at all musical it yet fell pleasantly on the ear.”

Secretary of War: 1817–25

In 1817, President James Monroe appointed Calhoun Secretary of War, where he served until 1825. Calhoun continued his role as a leading nationalist during the “Era of Good Feeling”. He proposed an elaborate program of national reforms to the infrastructure that would speed economic modernization. His first priority was an effective navy, including steam frigates, and in the second place a standing army of adequate size; and as further preparation for emergency “great permanent roads,” “a certain encouragement” to manufactures, and a system of internal taxation which would not be subject like customs duties to collapse by a war-time shrinkage of maritime trade. He spoke for a national bank, for internal improvements (such as harbors, canals and river navigation) and a protective tariff that would help the industrial Northeast and, especially, pay for the expensive new infrastructure. The word “nation” was often on his lips, and his conscious aim was to enhance national unity which he identified with national power.

After the war ended in 1815 the “Old Republicans” in Congress, with their Jeffersonian ideology for economy in the federal government, sought at every turn to reduce the operations and finances of the War Department. In 1817, the deplorable state of the War Department led four men to turn down requests to fill the Secretary of War position before Calhoun finally accepted the task. Political rivalry, namely, Calhoun’s political ambitions as well as those of William H. Crawford, the Secretary of the Treasury, over the pursuit of the 1824 presidency also complicated Calhoun’s tenure as War Secretary.

Calhoun proposed an expansible army similar to that of France under Napoleon, whereby a basic cadre of 6,000 officers and men could be expanded into 11,000 without adding additional officers or companies. Congress wanted an army of adequate size in case American interests in Florida or the west led to war with Britain or Spain. However the nation was satisfied by the diplomacy that produced the Convention of 1818 with Britain and the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819 with Spain, the need for a large army disappeared, and Calhoun could not prevent cutbacks in 1821.

As secretary, Calhoun had responsibility for management of Indian affairs. A reform-minded modernizer, he attempted to institute centralization and efficiency in the Indian department, but Congress either failed to respond to his reforms or responded with hostility. Calhoun’s frustration with congressional inaction, political rivalries, and ideological differences that dominated the late early republic spurred him to unilaterally create the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1824. He supervised the negotiation and ratification of 38 treaties with Indian tribes.

Vice Presidency

Election

Calhoun originally was a candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1824. After failing to win the endorsement of the South Carolina legislature, he decided to be a candidate for Vice President. Although no presidential candidate received a majority in the Electoral College and the election was ultimately resolved by the House of Representatives, the Electoral College elected Calhoun vice president by a landslide. Calhoun served four years under John Quincy Adams, and then, in 1828, won re-election as Vice President running with Andrew Jackson. He thus became one of two vice presidents to serve under two different presidents.

Nullification

Under Andrew Jackson, Calhoun’s vice presidency was also controversial. In time he developed a rift over policy with President Jackson, this time about hard cash, a policy which he considered to favor Northern financial interests.

Calhoun opposed an increase in the protective tariff. While Vice President in the John Quincy Adams administration (1825–1829), Andrew Jackson’s supporters devised a high tariff legislation that placed burdensome duties on selected New England imports. Calhoun had been assured that the northeastern interests would reject the Tariff of 1828, exposing New England (pro- Adams) congressmen to charges that they selfishly opposed legislation popular among Jacksonian Democrats in the west and Mid-Atlantic States. The southern legislators miscalculated and the Tariff of Abominations passed. As Vice President during this time, Calhoun presided over the Senate and took this role very seriously. The vote on the tariff was expected to come down to his tie-breaking vote. He claimed he would have voted against the tariff, but his vote was not necessary. Frustrated, Calhoun returned to his South Carolina plantation to write “South Carolina Exposition and Protest”, an essay rejecting the centralization philosophy.

Calhoun proposed the theory of a concurrent majority through the doctrine of nullification —- “the right of a State to interpose, in the last resort, in order to arrest an unconstitutional act of the General Government, within its limits.” Nullification can be traced back to arguments by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in writing the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798. They had proposed that states could nullify the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Jackson, who supported states’ rights but believed that nullification threatened the Union, opposed it. Calhoun differed from Jefferson and Madison in explicitly arguing for a state’s right to secede from the Union, as a last resort, in order to protect the liberty and sovereignty. James Madison rebuked supporters of nullification, stating that no state had the right to nullify federal law.

At the 1830 Jefferson Day dinner at Jesse Brown’s Indian Queen Hotel, Jackson proposed a toast and proclaimed, “Our federal Union, it must be preserved.” Calhoun replied, “the Union, next to our liberty, the most dear.”

In May 1830, Jackson discovered that Calhoun had asked President Monroe to censure then-General Jackson for his invasion of Spanish Florida in 1818. Calhoun was then serving as James Monroe’s Secretary of War (1817–1823). Jackson had invaded Florida during the First Seminole War without explicit public authorization from Calhoun or Monroe. Calhoun’s and Jackson’s relationship deteriorated further.

Calhoun defended his 1818 position. The feud between him and Jackson heated up as Calhoun informed the President that he risked another attack from his opponents. They started an argumentative correspondence, fueled by Jackson’s opponents, until Jackson stopped the letters in July 1830.

By February 1831, the break between Calhoun and Jackson was final. Responding to inaccurate press reports about the feud, Calhoun had published the letters in the United States Telegraph.

More upheaval came when his wife Floride Calhoun organized Cabinet wives against Peggy Eaton, wife of Secretary of War John Eaton. The scandal, which became known as the “Petticoat affair” or the “Peggy Eaton affair”, ripped apart the cabinet and created an intolerable situation for Jackson. Jackson saw attacks on Eaton stemming ultimately from the political opposition of Calhoun, and he used the affair to consolidate control over his cabinet, forcing the resignation of several members and ending Calhoun’s influence in the cabinet. Calhoun was the first vice president in U.S. history to resign from office, doing so on December 28, 1832.

Nullification Crisis

In 1832, states’ rights theory was put to the test in the Nullification Crisis, after South Carolina passed an ordinance that nullified federal tariffs. The tariffs favored northern manufacturing interests over southern agricultural concerns. The South Carolina legislature declared them unconstitutional. Calhoun had formed a political party in South Carolina explicitly known as the Nullifier Party.

In response to the South Carolina move, Congress passed the Force Bill, which empowered the President to use military power to force states to obey all federal laws. Jackson sent US Navy warships to Charleston harbor, and even talked of hanging Calhoun. South Carolina then nullified the Force Bill. Tensions cooled after both sides agreed to the Compromise Tariff of 1833, a proposal by Senator Henry Clay to change the tariff law in a manner which satisfied Calhoun, who by then was in the Senate. Calhoun’s speech on the Force Bill is perhaps the greatest example of his understanding of the Constitution’s structure.

Calhoun had earlier suggested that the doctrine of nullification could lead to secession. In his 1828 essay “South Carolina Exposition and Protest”, Calhoun argued that a state could veto any law it considered unconstitutional.

U.S. Senator

With his break with Jackson complete, in 1832, Calhoun ran for the Senate rather than continue as Vice President. Because he had expressed nullification beliefs during the crisis, his chances of becoming President were very low. After the Compromise Tariff of 1833 was implemented, the Nullifier Party, along with other anti-Jackson politicians, formed a coalition known as the Whig Party. Calhoun sided with the Whigs until he broke with key Whig Senator Daniel Webster over slavery, as well as the Whigs’ program of “internal improvements”. Many Southern politicians opposed these as benefiting Northern industrial interests at the expense of Southern interests. Whig Party leader Henry Clay sided with Daniel Webster on these issues. Calhoun achieved his greatest influence and most lasting fame as a Senator.

Slavery & Death

Calhoun led the pro-slavery faction in the Senate in the 1830s and 1840s, opposing both abolitionism and attempts to limit the expansion of slavery into the western territories; actively anti-Wilmot Proviso. He was a major advocate of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, which required the co-operation of local law enforcement officials in free states to return escaped slaves.

Calhoun was shaped by his father, Patrick Calhoun, a prosperous upstate planter who supported Independence during the American Revolutionary War but opposed ratification of the federal Constitution. The father was a staunch slaveholder who taught his son that one’s standing in society depended not merely on one’s commitment to the ideal of popular self-government but also on the ownership of a substantial number of slaves. Flourishing in a world in which slaveholding was a badge of civilization, Calhoun saw little reason to question its morality as an adult. He never visited Europe. Calhoun believed that the spread of slavery into the back country of his own state improved public morals by ridding the countryside of the shiftless poor whites who had once held the region back. He further believed that slavery instilled in the white who remained a code of honor that blunted the disruptive potential of private gain and fostered the civic-mindedness that lay near the core of the republican creed. From such a standpoint, the expansion of slavery into the backcountry decreased the likelihood for social conflict and postponed the declension when money would become the only measure of self-worth, as had happened in New England. Calhoun was thus firmly convinced that slavery was the key to the success of the American dream.

Whereas other Southern politicians had excused slavery as a necessary evil, in a famous speech on the Senate floor on February 6, 1837, Calhoun asserted that slavery was a “positive good.” He rooted this claim on two grounds: white supremacy and paternalism. All societies, Calhoun claimed, are ruled by an elite group which enjoys the fruits of the labor of a less-privileged group. Senator William Rives of Virginia earlier had referred to slavery as an evil that might become a “lesser evil” in some circumstances. Calhoun believed that conceded too much to the abolitionists: “I take higher ground. I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good—a positive good… I may say with truth, that in few countries so much is left to the share of the laborer, and so little exacted from him, or where there is more kind attention paid to him in sickness or infirmities of age. Compare his condition with the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe—look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poorhouse… I hold then, that there never has yet existed a wealthy and civilized society in which one portion of the community did not, in point of fact, live on the labor of the other.” A year later in the Senate (January 10, 1838), Calhoun repeated this defense of slavery as a “positive good”: “Many in the South once believed that it was a moral and political evil; that folly and delusion are gone; we see it now in its true light, and regard it as the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world.” Calhoun rejected the belief of Southern Whigs such as Henry Clay that all Americans could agree on the “opinion and feeling” that slavery was wrong, although they might disagree on the most practicable way to respond to that great wrong. Calhoun’s constitutional ideas acted as a viable conservative alternative to Northern appeals to democracy, majority rule and natural rights.

After a one-year service as Secretary of State (April 1, 1844 – March 10, 1845), Calhoun returned to the Senate in 1845. He participated in the political struggle over the expansion of slavery in the Western states. Regions were divided as to whether slavery should be allowed in the formerly Imperial Spanish and Mexican lands. The debate over this issue culminated in the Compromise of 1850.

Democratic Politics

To restore his national stature, Calhoun cooperated with Jackson’s successor Martin Van Buren, who became president in 1837. Democrats were very hostile to national banks, and the country’s bankers had joined the opposition Whig Party. The Democratic replacement was the “Independent Treasury” system, which Calhoun supported and which went into effect. Calhoun, like Jackson and Van Buren, attacked finance capitalism, which he saw as the common enemy of the Northern laborer, the Southern planter, and the small farmer everywhere. His goal, therefore, was to unite these groups in the Democratic Party, and to dedicate that party to states’ rights and agricultural interests as barriers against encroachment by government and big business. Unlike Jackson and Van Buren, Calhoun was never a true Jeffersonian. Unlike Jefferson, Calhoun rejected natural rights and emphases on democracy, equality, and liberty. A representative of the planter aristocracy, Calhoun rejected attempts at economic, social, or political leveling. For Calhoun, “protection” (order) was more important than freedom. Individual rights were something to be earned, not something bestowed by nature or God.

Foreign Policy

When Whig president William Henry Harrison died after a month in office in 1841, vice president John Tyler took office. Tyler was a former Democrat and broke bitterly with the Whigs, and named Calhoun Secretary of State in 1844. Public opinion was inflamed about the Oregon boundary dispute, claimed by both Britain and the U.S.. Calhoun compromised by splitting the area down the middle at the 49th parallel, ending the war threat.

Texas

Tyler and Calhoun were eager to annex the independent Republic of Texas, which wanted to join the Union. Texas was slave country and anti-slavery elements in the North denounced annexation as a plot to enlarge the Slave Power (that is, the excess political power controlled by slave owners). When the Senate could not muster a two-thirds vote to pass a treaty of annexation with Texas, Calhoun devised a joint resolution of the Houses of Congress, requiring only a simple majority; Texas joined the Union. Mexico had warned all along that it would go to war if Texas joined the Union; war broke out in 1846.

The evils of war and political parties

Calhoun was consistently opposed to the war with Mexico from its very beginning, arguing that an enlarged military effort would only feed the alarming and growing lust of the public for empire regardless of its constitutional dangers, bloat executive powers and patronage, and saddle the republic with a soaring debt that would disrupt finances and encourage speculation. Calhoun feared, moreover, that Southern slave owners would be shut out of any conquered Mexican territories (as almost happened with the Wilmot Proviso).

Anti-slavery Northerners denounced the war as a Southern conspiracy to expand slavery; Calhoun saw a conspiracy of Yankees to destroy the South. By 1847 he decided the Union was threatened by a totally corrupt party system. He believed that in their lust for office, patronage and spoils, politicians in the North pandered to the antislavery vote, especially during presidential campaigns, and politicians in the slave states sacrificed Southern rights in an effort to placate the Northern wings of their parties. Thus, the essential first step in any successful assertion of Southern rights had to be the jettisoning of all party ties. In 1848–49, Calhoun tried to give substance to his call for Southern unity. He was the driving force behind the drafting and publication of the “Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents.” It listed the alleged Northern violations of the constitutional rights of the South, then warned southern voters to expect forced emancipation of slaves in the near future, followed by their complete subjugation by an unholy alliance of unprincipled Northerners and blacks, and a South forever reduced to “disorder, anarchy, poverty, misery, and wretchedness.” Only the immediate and unflinching unity of Southern whites could prevent such a disaster. Such unity would either bring the North to its senses or lay the foundation for an independent South. But the spirit of union was still strong in the region and fewer than 40% of the southern congressmen signed the address, and only one Whig.

Southerners believed his warnings and read every political news story from the North as further evidence of the planned destruction of the southern way of life. The climax was the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860, which led immediately to the secession of South Carolina, followed by six other cotton states. They formed the new Confederate States of America, which, in accord with Calhoun’s theory, did not have any political parties.

Rejects Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850, devised by Clay and Democratic leader Stephen Douglas, was designed to solve the controversy over the status of slavery in the vast new territories acquired from Mexico. Calhoun, back in the Senate but too feeble to speak, wrote a blistering attack on the compromise. A friend read his speech, calling upon the Constitution, which upheld the South’s right to hold slaves; warning that the day “the balance between the two sections” was destroyed would be a day not far removed from disunion, anarchy, and civil war. Could the Union be preserved? Yes, easily; the North had only to will it to accomplish it; to agree to a restoration of the lost equilibrium of equal North–South representation in the Senate; and to cease “agitating” the slavery question. Calhoun had precedent and law on his side of the debate. But the North had time and rapid population growth due to industrialization, and the Compromise was passed.

Political philosophy

Agrarian Republicanism

Cheek (2001) distinguishes between two strands of American republican thought—the puritan tradition, based in New England, and the agrarian or South Atlantic tradition. Cheek argues that Calhoun is best understood as a representative of the South Atlantic tradition of agrarian republicanism. While the New England tradition stressed a politically centralized enforcement of moral and religious norms to secure civic virtue, the South Atlantic tradition relied on a decentralized moral and religious order based on the idea of “subsidiarity” (or localism). Cheek locates the fundamental principles of Calhoun’s republicanism in the “Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions” (1798) written by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Calhoun emphasizes the primacy of the idea of subsidiarity: popular rule is best expressed in local communities that are nearly autonomous while serving as units of a larger society.

Concurrent Majority

Calhoun’s basic concern for protecting the diverse interests of minority interests is expressed in his chief contribution to political science—the idea of a concurrent majority across different groups as distinguished from a numerical majority. According to the principle of a numerical majority, the will of the more numerous citizens should always rule, regardless of the burdens on the minority. Such a principle tends toward a consolidation of power in which the interests of the absolute majority always prevail over those of the minority. Calhoun believed that the great achievement of the American constitution was in checking the tyranny of a numerical majority through institutional procedures that required a concurrent majority, such that each important interest in the community must consent to the actions of government. To secure a concurrent majority, those interests that have a numerical majority must compromise with the interests that are in the minority. A concurrent majority requires a unanimous consent of all the major interests in a community, which is the only sure way of preventing majority tyranny. This idea supported Calhoun’s doctrine of interposition or nullification, in which the state governments could refuse to enforce or comply with a policy of the Federal government that threatened the vital interests of the states.

Historian Richard Hofstadter (1948) emphasizes that Calhoun’s conception of “minority” was very different from the minorities of a century later:

“Not in the slightest was concerned with minority rights as they are chiefly of interest to the modern liberal mind – the rights of dissenters to express unorthodox opinions, of the individual conscience against the State, least of all of ethnic minorities. At bottom he was not interested in any minority that was not a propertied minority. The concurrent majority itself was a device without relevance to the protection of dissent, designed to protect a vested interest of considerable power…it was minority privileges rather than rights that he really proposed to protect.”

Calhoun was chiefly concerned with protecting the interests of the Southern States (which he largely identified with the interests of their slaveholding elites), as a distinct and beleaguered minority among the members of the federal Union. However the idea of a concurrent majority as a protection for minority rights has gained wide acceptance in American political thought.

John C. Calhoun on the “concurrent majority” from his Disquisition (1850)

“If the whole community had the same interests, so that the interests of each and every portion would be so affected by the action of the government, that the laws which oppressed or impoverished one portion, would necessarily oppress and impoverish all others — or the reverse — then the right of suffrage, of itself, would be all-sufficient to counteract the tendency of the government to oppression and abuse of its powers….But such is not the case. On the contrary, nothing is more difficult than to equalize the action of the government, in reference to the various and diversified interests of the community; and nothing more easy than to pervert its powers into instruments to aggrandize and enrich one or more interests by oppressing and impoverishing the others; and this too, under the operation of laws, couched in general terms — and which, on their face, appear fair and equal…..Such being the case, it necessarily results, that the right of suffrage, by placing the control of the government in the community must . . . lead to conflict among its different interests — each striving to obtain possession of its powers, as the means of protecting itself against the others — or of advancing its respective interests, regardless of the interests of others. For this purpose, a struggle will take place between the various interests to obtain a majority, in order to control the government. If no one interest be strong enough, of itself, to obtain it, a combination will be formed…. the community will be divided into two great parties — a major and minor — between which there will be incessant struggles on the one side to retain, and on the other to obtain the majority — and, thereby, the control of the government and the advantages it confers.”

Disquisition on Government

The Disquisition on Government is a 100-page abstract treatise that comprises Calhoun’s definitive and fully elaborated ideas on government; he worked on it intermittently for six years before it was finished in 1849. It systematically presents his arguments that (1) a numerical majority in any government will typically impose a despotism over a minority unless some way is devised to secure the assent of all classes, sections, and interests and (2) that innate human depravity would debase government in a democracy.

Calhoun offered the concurrent majority as the key to achieving consensus, a formula by which a minority interest had the option to nullify objectionable legislation passed by a majority interest. The doctrine would be made effective by this tactic of nullification, a veto that would suspend the law within the boundaries of the state.

Veto power was linked to the right of secession; with secession came the threat of anarchy and social chaos. Constituencies would call for compromise to prevent this outcome. With a concurrent majority in place, the US Constitution would no longer exert collective authority over the various states and cease to be the “supreme law of the land” (Article 4, Clause 2).

The mechanisms for his system are convincing if one shares Calhoun’s conviction that a functioning concurrent majority never leads to stalemate in the legislature; rather, talented statesmen, practiced in the arts of conciliation and compromise would pursue “the common good”, however explosive the issue. His formula promised to produce laws satisfactory to all interests. The ultimate goal of these mechanism was to facilitate the authentic will of the white populace. Calhoun explicitly rejected the founding principles of equality in the Declaration of Independence, denying that humanity is born free and equal in shared human nature and basic needs. He regarded this precept as “the most false and dangerous of all political errors”. States could constitutionally take action to free themselves from an overweening government, but slaves as individuals or interest groups could not do so.

Calhoun’s assumed that with the establishment of a concurrent majority, interest groups would influence their own representatives sufficiently to have a voice in public affairs; the representatives would perform strictly as high-minded public servants. Under this scenario, the political leadership would improve and persist; corruption and demagoguery would subside; and the interests of the people would be honored. This introduces the second theme in the Disquisition and a counterpoint to his concept of the concurrent majority: political corruption.

Calhoun considered the concurrent majority essential to provide structural restraints to counter his belief that “a vast majority of mankind is entirely biased by motives of self-interest and that by this interest must be governed.” This innate selfishness, which he viewed as axiomatic, would inevitably emerge when government revenue became available to political parties for distribution as patronage.

Politicians and bureaucrats would succumb to the lure of government lucre accumulated through taxation, tariff duties and public land sales. Even a diminishment of massive revenue effected through nullification by the permanent minority would not eliminate these temptations. A robust national defense – acknowledged by all interests as essential to national security– would require significant military expenditures. These funds alone would be sufficient to entice political leaders into abandoning the interests of their constituents in favor of serving personal and party interests.

Calhoun predicted that electioneering, political conspiracies and outright fraud would be employed to mislead and distract a gullible public; inevitably, perfidious demagogues would come to rule the political scene. A decline in authority among the principal statesmen would follow, and, ultimately, the eclipse of the concurrent majority.

Calhoun contended that however confused and misled the masses were by political opportunists, any efforts to impose majority rule upon a minority would be thwarted by a minority veto. What Calhoun fails to explain, according to historian William W. Freehling, is how a compromise would be achieved in the aftermath of a minority veto, when the ubiquitous demagogues betray their constituencies and abandon the concurrent majority altogether. Calhoun’s two key concepts – the maintenance of the concurrent majority by high-minded statesmen on the one hand; and the inevitable rise of demagogues who undermine consensus on the other – are never reconciled or resolved in the Disquisition.

South Carolina and other Southern states, in the three decades preceding the Civil War, had provided legislatures in which the vested interests of land and slaves dominated in the upper houses, while the popular will of the numerical majority prevailed in the lower houses. There was little opportunity for demagogues to establish themselves in this political milieu – the democratic component among the people was too weak to sustain a plebeian politician. The conservative statesmen – the slaveholding gentry – retained control over the political apparatus. William W. Freehling described the nature of the democracy that existed in antebellum South Carolina:

he apportionment of legislative seats gave the small majority of low country aristocrats control of the senate and a disproportionate influence in the house. Political power in South Carolina was uniquely concentrated in a legislature of large property holders who set state policy and selected the men to administer it. The characteristics of South Carolina politics cemented the control of upper class planters. Elections to the state legislature – the one control the masses could exert over the government – were often uncontested and rarely allowed the “plebian” a clear choice between two parties or policies.

This was done in conscious acceptance of the doctrine of the Disquisition.

The Disquisition was published shortly after his death as was his other book, Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States.

State Sovereignty and the “Calhoun Doctrine”

In the 1840s three interpretations of the Constitutional powers of Congress to deal with slavery in territories emerged: the “free-soil doctrine,” the “Calhoun doctrine,” and “popular sovereignty”. The Free Soilers said Congress had the power to outlaw slavery in the territories. The Popular Sovereignty position said the voters living there should decide. The Calhoun doctrine said Congress could never outlaw slavery in the territories.

In what historian Robert R. Russell calls the “Calhoun Doctrine,” Calhoun argued that the Federal Government’s role in the territories was only that of the trustee or agent of the several sovereign states: it was obliged not to discriminate among the states and hence was incapable of forbidding the bringing into any territory of anything that was legal property in any state. Calhoun argued that citizens from every state had the right to take their property to any territory. Congress, he asserted, had no authority to place restrictions on slavery in the territories. As Constitutional historian Hermann von Holst noted, “Calhoun’s doctrine made it a solemn constitutional duty of the United States government and of the American people to act as if the existence or non-existence of slavery in the Territories did not concern them in the least.” The Calhoun Doctrine was vehemently opposed by the Free Soil forces, who merged into the new Republican Party around 1854.

Memorials

During the Civil War, the Confederate government honored Calhoun on a one-cent postage stamp, which was printed in 1862 but was never officially released.

The territory of Minnesota honored Calhoun by naming Lake Calhoun after him, which is today one lake of the Chain of Lakes in Minneapolis.

Calhoun was also honored by his alma mater, Yale University, which named one of its undergraduate residence halls “Calhoun College”. A sculpture of Calhoun appears on the exterior of Harkness Tower, a prominent campus landmark.

The Clemson University campus in South Carolina occupies the site of Calhoun’s Fort Hill plantation, which he bequeathed to his wife and daughter. They sold it and its 50 slaves to a relative. They received $15,000 for the 1,100 acres (450 ha) and $29,000 for the slaves (they were valued at about 600 USD apiece). When that owner died, Thomas Green Clemson foreclosed the mortgage. He later bequeathed the property to the state for use as an agricultural college to be named after him.

A wide range of places, streets and schools were named after Calhoun, as may be seen on the above list. The “Immortal Trio” were memorialized with streets in Uptown New Orleans. Calhoun Landing, on the Santee-Cooper River in Santee, South Carolina, was named after him. The Calhoun Monument was erected in Charleston, South Carolina. The USS John C. Calhoun was a Fleet Ballistic Missile nuclear submarine, in commission from 1963 to 1994.

In 1957, United States Senators honored Calhoun as one of the “five greatest senators of all time.”

“

“The whole South is the grave of Calhoun.”

”

— Yankee Soldier (1865) from the title page of Margaret Coit’s John C. Calhoun :