OverView

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard ( Danish; 5 May 1813 11 November 1855) was a Danish philosopher , theologian, poet, social critic and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical texts on organized religion, Christendom, morality, ethics, psychology, and the philosophy of religion, displaying a fondness for metaphor, irony and parables. Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives as a “single individual”, giving priority to concrete human reality over abstract thinking and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment. He was against literary critics who defined idealist intellectuals and philosophers of his time, and thought that Swedenborg,Hegel,Goethe,Fichte, Schelling, Schlegel and Hans Christian Andersen were all “understood” far too quickly by “scholars”.

Kierkegaard’s theological work focuses on Christian ethics, the institution of the Church, the differences between purely objective proofs of Christianity, the infinite qualitative distinction between man and God, and the individual’s subjective relationship to the God-Man Jesus the Christ, which came through faith. Much of his work deals with Christian love. He was extremely critical of the practice of Christianity as a state religion, primarily that of the Church of Denmark. His psychological work explored the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with life choices.

Kierkegaard’s early work was written under various pseudonyms that he used to present distinctive viewpoints and to interact with each other in complex dialogue. He explored particularly complex problems from different viewpoints, each under a different pseudonym. He wrote many Upbuilding Discourses under his own name and dedicated them to the “single individual” who might want to discover the meaning of his works. Notably, he wrote: “Science and scholarship want to teach that becoming objective is the way. Christianity teaches that the way is to become subjective, to become a subject.” While scientists can learn about the world by observation, Kierkegaard emphatically denied that observation could reveal the inner workings of the world of the spirit.

Some of Kierkegaard’s key ideas include the concept of “subjective and objective truths“, the knight of faith, the recollection and repetition dichotomy, angst, the infinite qualitative distinction, faith as a passion, and the three stages on life’s way. Kierkegaard wrote in Danish and the reception of his work was initially limited to Scandinavia, but by the turn of the 20th century his writings were translated into French, German, and other major European languages. By the mid-20th century, his thought exerted a substantial influence on philosophy, theology, and Western culture.

Reception

19th century reception

In September 1850, the Western Literary Messenger wrote: “While Martensen with his wealth of genius casts from his central position light upon every sphere of existence, upon all the phenomena of life, Søren Kierkegaard stands like another Simon Stylites, upon his solitary column, with his eye unchangeably fixed upon one point.” In 1855, the Danish National Church published his obituary. Kierkegaard did have an impact there judging from the following quote from their article: “The fatal fruits which Dr. Kierkegaard show to arise from the union of Church and State, have strengthened the scruples of many of the believing laity, who now feel that they can remain no longer in the Church, because thereby they are in communion with unbelievers, for there is no ecclesiastical discipline.”

Changes did occur in the administration of the Church and these changes were linked to Kierkegaard’s writings. The Church noted that dissent was “something foreign to the national mind.” On 5 April 1855 the Church enacted new policies: “every member of a congregation is free to attend the ministry of any clergyman, and is not, as formerly, bound to the one whose parishioner he is”. In March 1857, compulsory infant baptism was abolished. Debates sprang up over the King’s position as the head of the Church and over whether to adopt a constitution. Grundtvig objected to having any written rules. Immediately following this announcement the “agitation occasioned by Kierkegaard” was mentioned. Kierkegaard was accused of Weigelianism and Darbyism, but the article continued to say, “One great truth has been made prominent, viz (namely): That there exists a worldly-minded clergy; that many things in the Church are rotten; that all need daily repentance; that one must never be contented with the existing state of either the Church or her pastors.”

Hans Martensen was the subject of a Danish article, Dr. S. Kierkegaard against Dr. H. Martensen By Hans Peter Kofoed-Hansen (18131893) that was published in 1856 (untranslated) and Martensen mentioned him extensively in Christian Ethics, published in 1871. “Kierkegaard’s assertion is therefore perfectly justifiable, that with the category of “the individual” the cause of Christianity must stand and fall; that, without this category, Pantheism had conquered unconditionally. From this, at a glance, it may be seen that Kierkegaard ought to have made common cause with those philosophic and theological writers who specially desired to promote the principle of Personality as opposed to Pantheism. This is, however, far from the case. For those views which upheld the category of existence and personality, in opposition to this abstract idealism, did not do this in the sense of an eitheror, but in that of a bothand. They strove to establish the unity of existence and idea, which may be specially seen from the fact that they desired system and totality. Martensen accused Kierkegaard and Alexandre Vinet of not giving society its due. He said both of them put the individual above society, and in so doing, above the Church.” Another early critic was Magnús Eiríksson who criticized Martensen and wanted Kierkegaard as his ally in his fight against speculative theology.

“August Strindberg was influenced by the Danish individualistic philosopher Kierkegaard while a student at Uppsala University (18671870) and mentioned him in his book Growth of a Soul as well as Zones of the Spirit (1913). Edwin Bjorkman credited Kierkegaard as well as Henry Thomas Buckle and Eduard von Hartmann with shaping Strindberg’s artistic form until he was strong enough to stand wholly on his own feet.” The dramatist Henrik Ibsen is said to have become interested in Kierkegaard as well as the Norwegian national writer and poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (18321910) who named one of his characters Søren Pedersen in his 1890 book In God’s Way. Kierkegaard’s father’s name was Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard.

Several of Kierkegaard’s works were translated into German from 1861 onward, including excerpts from Practice in Christianity (1872), from Fear and Trembling and Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1874), Four Upbuilding Discourses and Christian Discourses (1875), and The Lillis of the Field and the Birds of the Air (1876) according to Kierkegaard’s International Reception: Northern and Western Europe: Toma I, by John Stewart, see p. 388ff’The Sickness Unto Death, 1881Twelve speeches by Søren Kierkegaard, by Julius Fricke, 1886Stages on Life’s Way, 1886 (Bärthold)

Otto Pfleiderer in The Philosophy of Religion: On the Basis of Its History (1887), claimed that Kierkegaard presented an anti-rational view of Christianity. He went on to assert that the ethical side of a human being has to disappear completely in his one-sided view of faith as the highest good. He wrote, “Kierkegaard can only find true Christianity in entire renunciation of the world, in the following of Christ in lowliness and suffering especially when met by hatred and persecution on the part of the world. Hence his passionate polemic against ecclesiastical Christianity, which he says has fallen away from Christ by coming to a peaceful understanding with the world and conforming itself to the world’s life. True Christianity, on the contrary, is constant polemical pathos, a battle against reason, nature, and the world; its commandment is enmity with the world; its way of life is the death of the naturally human.”

An article from an 1889 dictionary of religion revealed a good idea of how Kierkegaard was regarded at that time, stating: “Having never left his native city more than a few days at a time, excepting once, when he went to Germany to study Schelling’s philosophy. He was the most original thinker and theological philosopher the North ever produced. His fame has been steadily growing since his death, and he bids fair to become the leading religio-philosophical light of Germany, not only his theological, but also his aesthetic works have of late become the subject of universal study in Europe.”

Early 20th century reception

The first academic to draw attention to Kierkegaard was fellow Dane Georg Brandes, who published in German as well as Danish. Brandes gave the first formal lectures on Kierkegaard in Copenhagen and helped bring him to the attention of the European intellectual community. Brandes published the first book on Kierkegaard’s philosophy and life, Søren Kierkegaard, ein literarisches Charakterbild. Autorisirte deutsche Ausg (1879) and compared him to Hegel and Tycho Brahe in Reminiscences of my Childhood and Youth (1906). Brandes also discussed the Corsair Affair in the same book. Brandes opposed Kierkegaard’s ideas in the 1911 edition of the Britannica. Brandes compared Kierkegaard to Nietzsche as well. Brandes also mentioned Kierkegaard extensively in volume 2 of his 6 volume work, Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature (1872 in German and Danish, 1906 English).

There are two types of the artistic soul. There is the one which needs many varying experiences and constantly changing models, and which instantly gives a poetic form to every fresh incident. There is the other which requires amazingly few outside elements to fertilise it, and for which a single life circumstance, inscribed with sufficient force, can furnish a whole wealth of ever-changing thought and modes of expression. Soren Kierkegaard among writers, and Max Klinger among painters, are both great examples of the latter type. To which did Shakespeare belong? William Shakespeare; a critical study, by George Brandes. 1898 p. 195

During the 1890s, Japanese philosophers began disseminating the works of Kierkegaard, from the Danish thinkers.Tetsuro Watsuji was one of the first philosophers outside of Scandinavia to write an introduction on his philosophy, in 1915.

Harald Høffding wrote an article about him in A brief history of modern philosophy (1900). Høffding mentioned Kierkegaard in Philosophy of Religion 1906, and the American Journal of Theology (1908) printed an article about Hoffding’s Philosophy of Religion. Then Høffding repented of his previous convictions in The problems of philosophy (1913). Høffding was also a friend of the American philosopher William James, and although James had not read Kierkegaard’s works, as they were not yet translated into English, he attended the lectures about Kierkegaard by Høffding and agreed with much of those lectures. James’ favorite quote from Kierkegaard came from Høffding: “We live forwards but we understand backwards”. William James wrote:

“We live forward, we understand backward, said a Danish writer; and to understand life by concepts is to arrest its movement, cutting it up into bits as if with scissors, and, immobilizing these in our logical herbarium where, comparing them as dried specimens, we can ascertain which of them statically includes or excludes which other. This treatment supposes life to have already accomplished itself, for the concepts, being so many views taken after the fact, are retrospective and post mortem. Nevertheless, we can draw conclusions from them and project them into the future. We cannot learn from them how life made itself go, or how it will make itself go; but, on the supposition that its ways of making itself go are unchanging, we can calculate what positions of imagined arrest it will exhibit hereafter under given conditions.” William James, A Pluralistic Universe, 1909, p. 244

Kierkegaard wrote of moving forward past the irresolute good intention:

The yes of the promise is sleep-inducing, but the no, spoken and therefore audible to oneself, is awakening, and repentance is usually not far away. The one who says, “I will, sir,” is at the same moment pleased with himself; the one who says no becomes almost afraid of himself. But this difference if very significant in the first moment and very decisive in the next moment; yet if the first moment is the judgment of the momentary, the second moment is the judgment of eternity. This is precisely why the world is so inclined to promises, inasmuch as the world is the momentary, and at the moment a promise looks very good. This is why eternity is suspicious of promises, just as it is suspicious of everything momentary. And so it is also with the one who, rich in good intentions and quick to promise, moves backward further and further away from the good. By means of the intention and the promise, he is facing in the direction of the good, is turned toward the good but is moving backward further and further away from it. With every renewed intention and promise it looks as if he took a step forward, and yet he is not merely standing still, but he is actually taking a step backward. The intention taken in vain, the unfulfilled promise, leaves despondency, dejection, that in turn perhaps soon blazes up into an even more vehement intention, which leaves only greater listlessness. Just as the alcoholic continually needs a stronger and stronger stimulant-in order to become intoxicated, likewise the one who has become addicted to promises and good intentions continually needs more and more stimulation-in order to go backward. Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love, Hong p. 93-94 (1850)

One thing James did have in common with Kierkegaard was respect for the single individual, and their respective comments may be compared in direct sequence as follows: “A crowd is indeed made up of single individuals; it must therefore be in everyone’s power to become what he is, a single individual; no one is prevented from being a single individual, no one, unless he prevents himself by becoming many. To become a crowd, to gather a crowd around oneself, is on the contrary to distinguish life from life; even the most well-meaning one who talks about that, can easily offend a single individual.” In his book A Pluralistic Universe, James stated that, “Individuality outruns all classification, yet we insist on classifying every one we meet under some general label. As these heads usually suggest prejudicial associations to some hearer or other, the life of philosophy largely consists of resentments at the classing, and complaints of being misunderstood. But there are signs of clearing up for which both Oxford and Harvard are partly to be thanked.”

The Encyclopaedia of religion and ethics had an article about Kierkegaard in 1908. The article began:

“The life of Søren Kierkegaard has but few points of contact with the external world; but there were, in particular, three occurrencesa broken engagement, an attack by a comic paper, and the use of a word by H.L. Martensenwhich must be referred to as having wrought with extraordinary effect upon his peculiarly sensitive and high-strung nature. The intensity of his inner life, againwhich finds expression in his published works, and even more directly in his notebooks and diaries (also published)cannot be properly understood without some reference to his father.”

Friedrich von Hügel wrote about Kierkegaard in his 1913 book, Eternal life: a study of its implications and applications, where he said: “Kierkegaard, the deep, melancholy, strenuous, utterly uncompromising Danish religionist, is a spiritual brother of the great Frenchman, Blaise Pascal, and of the striking English Tractarian, Hurrell Froude, who died young and still full of crudity, yet left an abiding mark upon all who knew him well.”

John George Robertson wrote an article called Soren Kierkegaard in 1914: “Notwithstanding the fact that during the last quarter of a century, we have devoted considerable attention to the literatures of the North, the thinker and man of letters whose name stands at the head of the present article is but little known to the English-speaking world. The Norwegians, Ibsen and Bjørnson, have exerted a very real power on our intellectual life, and for Bjørnson we have cherished even a kind of affection. But Kierkegaard, the writer who holds the indispensable key to the intellectual life of Scandinavia, to whom Denmark in particular looks up as her most original man of genius in the nineteenth century, we have wholly overlooked.” Robertson wrote previously in Cosmopolis (1898) about Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.Theodor Haecker wrote an essay titled, Kierkegaard and the Philosophy of Inwardness in 1913 and David F. Swenson wrote a biography of Søren Kierkegaard in 1920.Lee M. Hollander translated parts of Either/Or, Fear and Trembling, Stages on Life’s Way, and Preparations for the Christian Life (Practice in Christianity) into English in 1923, with little impact. Swenson wrote about Kierkegaard’s idea of “armed neutrality” in 1918 and a lengthy article about Søren Kierkegaard in 1920. Swenson stated: “It would be interesting to speculate upon the reputation that Kierkegaard might have attained, and the extent of the influence he might have exerted, if he had written in one of the major European languages, instead of in the tongue of one of the smallest countries in the world.”

Austrian psychologist Wilhelm Stekel (18681940) referred to Kierkegaard as the “fanatical follower of Don Juan, himself the philosopher of Don Juanism” in his book Disguises of Love. German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers (18831969) stated he had been reading Kierkegaard since 1914 and compared Kierkegaard’s writings with Friedrich Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind and the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. Jaspers saw Kierkegaard as a champion of Christianity and Nietzsche as a champion for atheism. Later, in 1935, Karl Jaspers emphasized Kierkegaard’s (and Nietzsche’s) continuing importance for modern philosophy

German and English translators of Kierkegaard’s works

Hermann Gottsche published Kierkegaard’s Journals in 1905. It had taken academics 50 years to arrange his journals. Kierkegaard’s main works were translated into German by Christoph Schrempf from 1909 onwards.Emmanuel Hirsch released a German edition of Kierkegaard’s collected works from 1950 onwards. Both Harald Hoffding’s and Schrempf’s books about Kierkegaard were reviewed in 1892.

In the 1930s, the first academic English translations, by Alexander Dru, David F. Swenson, Douglas V. Steere, and Walter Lowrie appeared, under the editorial efforts of Oxford University Press editor Charles Williams, one of the members of the Inklings.Thomas Henry Croxall, another early translator, Lowrie, and Dru all hoped that people would not just read about Kierkegaard but would actually read his works. Dru published an English translation of Kierkegaard’s Journals in 1958;Alastair Hannay translated some of Kierkegaard’s works. From the 1960s to the 1990s, Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong translated his works more than once. The first volume of their first version of the Journals and Papers (Indiana, 19671978) won the 1968 U.S. National Book Award in category Translation. They both dedicated their lives to the study of Søren Kierkegaard and his works, which are maintained at the Howard V. and Edna H. Hong Kierkegaard Library.Jon Stewart from the University of Copenhagen has written extensively about Søren Kierkegaard.

Kierkegaards influence on Karl Barths early theology

Kierkegaards influence on Karl Barths early theology is evident in The Epistle to the Romans. The early Barth read at least three volumes of Kierkegaards works: Practice in Christianity, The Moment, and an Anthology from his journals and diaries. Almost all key terms from Kierkegaard which had an important role in The Epistle to the Romans can be found in Practice in Christianity. The concept of the indirect communication, the paradox, and the moment of Practice in Christianity, in particular, confirmed and sharpened Barths ideas on contemporary Christianity and the Christian life.

Wilhelm Pauk wrote in 1931 (Karl Barth Prophet Of A New Christianity) that Kierkegaard’s use of the Latin phrase Finitum Non Capax Infiniti (the finite does not (or cannot) comprehend the infinite) summed up Barth’s system. David G. Kingman and Adolph Keller each discussed Barth’s relationship to Kierkegaard in their books, The Religious Educational Values in Karl Barth’s Teachings (1934) and Karl Barth and Christian Unity (1933). Keller notes the splits that happen when a new teaching is introduced and some assume a higher knowledge from a higher source than others. But Kierkegaard always referred to the equality of all in the world of the spirit where there is neither “sport” nor “spook” or anyone who can shut you out of the world of the spirit except yourself. All are chosen by God and equal in His sight. The Expectancy of Faith,” Before this faith came, we were held prisoners by the law, locked up until faith should be revealed. So the law was put in charge to lead us to Christ that we might be justified by faith. Now that faith has come, we are no longer under the supervision of the law. You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise. The Bible NIV” Galatians 3:2329; “In the world of spirit to become ones own master, is the highest and in love to help someone toward that, to become himself, free, independent, his own master, to help him stand alone that is the greatest beneficence. The greatest beneficence, to help the other to stand alone, cannot be done directly.” “If a person always keeps his soul sober and alert in this idea, he will never go astray in his outlook on life and people or “combine respect for status of persons with his faith.” Show no partiality as you hold the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ. (James 2.1) Then he will direct his thoughts toward God, and his eye will not make the mistake of looking for differences in the world instead of likeness with God.

It was in his study of Paul that he found his first peace of mind. He was fascinated by the revelation of the power of the Holy Spirit when it once touched a man; at the completeness with which it overwhelms and keeps its chosen ones loyal. He conceived of Paul as one upon whom God had laid His hand’ Barth writes: “The man Paul evidently sees and hears something which is above everything, which is absolutely beyond the range of my observation and measure of my thought.” Following this observation Barth too became a “listener” and in that moment was born the “Theology of Crisis.” Besides affecting Barth deeply, the philosophy of Kierkegaard has found voice in the works of Ibsen, Unamuno, and Heidegger, and its sphere of influence seems to be growing in ever widening circles. The principle contribution of Kierkegaard to Barth is the dualism of time and eternity which Kierkegaard phrases: “The infinite qualitative difference between time and eternity.”

Wherever Kierkegaard is understood, opposition is aroused to organized ecclesiasticism, to the objective treatment of religious questions, to the sovereignty of man, whether it be called idealism or theology of mystical experience. In this Kierkegaard circle of young pastors and pupils of Geismar there arose not only resistance against the teacher himself, whom they accused of failing to present Kierkegaards ideas as sufficiently radical, but also against the prevalent work of the church as such. The work with the youth, the work with Home Missions appears as superficial church business. In Grundtvigianism they frequently saw secularized piety, which had gone over to a concern with all sorts of cultural possessions. The majesty of God seemed to have been preserved too little and the institution of the church seemed to have taken over the meaning of the existential meeting with the transcendent God. In this opposition to the prevalent church life the thoughts of Kierkegaard have certainly remained alive. However, they became effective only when their reinforced echo from foreign lands reached Denmark. This effect was more marked when Barthianism became known. Into this group of dissatisfied, excited radicals Barthian thought penetrated with full force. The inward distress, the tension and the preparation of Kierkegaard made them receptive to the new. A magazine entitled the Tidenverv (The Turn of the Times), has been their journal since 1926. Especially the Student Christian Movement became the port of invasion for the new thought. But this invasion has been split completely into two camps which vehemently attack each other. Indictment was launched against the old theology. The quiet work of the church was scorned as secularization of the message or as emotional smugness, which had found a place in Home Missions despite all its call to repentance.

Kierkegaard and the early Barth think that in Christianity, direct communication is impossible because Christ appears incognito. For them Christ is a paradox, and therefore one can know him only in indirect communication. They are fully aware of the importance of the moment when the human being stands before God, and is moved by him alone from time to eternity, from the earth to which (s)he belongs to the heaven where God exists. But Kierkegaard stressed the single individual in the presence of God in time in his early discourses and wrote against speculative arguments about whether or not one individual, no matter how gifted, can ascertain where another stood in relation to God as early as his Two Upbuilding Discourses of 1843 where he wrote against listening to speculative Christians:

The expectation of faith is then victory, and this expectation cannot be disappointed unless a man disappoints himself by depriving himself of expectation; like the one who foolishly supposed that he had lost faith, or foolishly supposed that some individual had taken it from him; or like the one who sought to delude himself with the idea that there was some special power which could deprive a man of his faith; who found satisfaction in the vain thought that this was precisely what had happened to him, found joy in frightening others with the assurance that some such power did exist that made sport of the noblest in man, and empowered the one who was thus tested to ridicule others. Søren Kierkegaard, Two Edifying Discourses 1843, Swenson trans., 1943 p. 30

Barth endorses the main theme from Kierkegaard but also reorganizes the scheme and transforms the details. Barth expands the theory of indirect communication to the field of Christian ethics; he applies the concept of unrecognizability to the Christian life. He coins the concept of the “paradox of faith” since the form of faith entails a contradictory encounter of God and human beings. He also portrayed the contemporaneity of the moment when in crisis a human being desperately perceives the contemporaneity of Christ. In regard to the concept of indirect communication, the paradox, and the moment, the Kierkegaard of the early Barth is a productive catalyst.

Later 20th century reception

William Hubben compared Kierkegaard to Dostoevsky in his 1952 book Four Prophets of Our Destiny, later titled Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka.

Logic and human reasoning are inadequate to comprehend truth, and in this emphasis Dostoevsky speaks entirely the language of Kierkegaard, of whom he had never heard. Christianity is a way of life, an existential condition. Again, like Kierkegaard, who affirmed that suffering is the climate in which mans soul begins to breathe. Dostoevsky stresses the function of suffering as part of Gods revelation of truth to man. Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka by William Hubben 1952 McMillan p. 83

In 1955 Morton White wrote about the word “exists” and Kierkegaard’s idea of God’s is-ness.

The word exists is one of the most pivotal and controversial in philosophy. Some philosophers think of it as having one meaning: the sense in which we say that this book exists, that God does or does not exist, that there exist odd numbers between 8 and 20, that a characteristic like redness exists as well as things that are red, that the American government exists as well as the physical building in which the government is housed, that minds exist as well as bodies. And when the word exists is construed in this unambiguous way, many famous disputes in the history of philosophy and theology appear to be quite straightforward. Theists affirm that God exists while atheists deny the very same statement; materialists say that matter exists while some idealists think that it is illusory; nominalists, as they are called, deny the existence of characteristics like redness while platonic realists affirm it; some kinds of behaviorists deny that there are minds inside bodies. There is, however, a tendency among some philosophers, to insist that the word exists is ambiguous and therefore that some of these disputes are not disputes at all but merely the results of mutual misunderstanding, of a failure to see that certain things are said to exist in one sense while others exist in another. One of the outstanding efforts of this kind in the twentieth century occurs in the early writings of realists who maintained that only concrete things in space and time exist, while abstract characteristics of things or relations between them should be said to subsist. This is sometimes illustrated by pointing out that while Chicago and St. Louis both exist at definite places, the relation more populous than which holds between them exists neither in Chicago nor in St. Louis nor in the area between them, but is nevertheless something about which we can speak, something that is usually assigned to a timeless and spaceless realm like that of which Plato spoke. On this view, however, human minds or personalities are also said to exist in spite of being non-material. In short, the great divide is between abstract subsistents and concrete existents, but both human personalities and physical objects are existents and do not share in the spacelessness and timelessness of platonic ideas.

So far as one can see, Kierkegaard too distinguishes different senses of exists, except that he appears to need at least three distinct senses for which he should supply three distinct words. First of all he needs one for statements about God, and so he says that God is. Secondly, and by contrast, persons or personalities are said to exist. It would appear then that he needs some third term for physical objects, which on his view are very different from God and persons, but since existentialists dont seem to be very interested in physical objects or mere things, they appear to get along with two. The great problem for Kierkegaard is to relate Gods is-ness, if I may use that term for the moment, to human existence, and this he tries to solve by appealing to the Incarnation. Christs person is the existent outgrowth of God who is. By what is admittedly a mysterious process the abstract God enters a concrete existent. We must accept this on faith and faith alone, for clearly it cannot be like the process whereby one existent is related to another; it involves a passage from one realm to another which is not accessible to the human mind, Christians who lacked this faith and who failed to live by it were attacked by Kierkegaard; this was the theological root of his violent criticism of the Established Church of Denmark. It is one source of his powerful influence on contemporary theology.

- 20th Century Philosophers, The Age of Analysis, selected with introduction and commentary by Morton White 1955 p. 118-121 Houghton Mifflin Co

John Daniel Wild noted as early as 1959 that Kierkegaard’s works had been “translated into almost every important living language including Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, and it is now fair to say that his ideas are almost as widely known and as influential in the world as those of his great opponent Hegel, still the most potent of world philosophers.”

Mortimer J. Adler wrote the following about Kierkegaard in 1962:

For Kierkegaard, man is essentially an individual, not a member of a species or race; and ethical and religious truth is known through individual existence and decision-through subjectivity, not objectivity. Systems of thought and a dialectic such as Hegels are matters merely of thought, which cannot comprise individual existence and decision. Such systems leave out, said Kierkegaard, the unique and essential spermatic point, the individual, ethically and religiously conceived, and existentially accentuated. Similarly in the works of the American author Henry David Thoureau, writing at the same time as Kierkegaard, there is an emphasis on the solitary individual as the bearer of ethical responsibility, who, when he is right, carries the preponderant ethical weight against the state, government, and a united public opinion, when they are wrong. The solitary individual with right on his side is always a majority of one. Ethics, the study of moral values, by Mortimer J. Adler and Seymour Cain. Pref. by William Ernest Hocking. 1962 p. 252

In 1964 Life Magazine traced the history of existentialism from Heraclitus (500BC) and Parmenides over the argument over The Unchanging One as the real and the state of flux as the real. From there to the Old Testament Psalms and then to Jesus and later from Jacob Boehme (15751624) to Rene Descartes (15961650) and Blaise Pascal (16231662) and then on to Nietzsche and Paul Tillich. Dostoevski and Camus are attempts to rewrite Descartes according to their own lights and Descartes is the forefather of Sartre through the fact that they both used a “literary style.” The article goes on to say,

But the orthodox, textbook precursor of modern existentialism was the Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard (18131855), a lonely, hunchbacked writer who denounced the established church and rejected much of the then-popular German idealism in which thought and ideas, rather than things perceived through the senses, were held to constitute reality. He built a philosophy based in part on the idea of permanent cleavage between faith and reason. This was an existentialism which still had room for a God whom Sartre later expelled, but which started the great pendulum-swing toward the modern concepts of the absurd. Kierkegaard spent his life thinking existentially and converting remarkably few to his ideas. But when it comes to the absurdity of existence, war is a great convincer; and it was at the end of World War I that two German philosophers, Karl Jaspers and Martin Heidegger, took up Kierkegaards ideas, elaborated and systematized them. By the 1930s Kierkegaards thinking made new impact on French intellectuals who, like Sartre, were nauseated by the static pre-Munich hypocrisy of the European middle class. After World War II, with the human condition more precarious than ever, with humanity facing the mushroom-shaped ultimate absurdity, existentialism and our time came together in Jean-Paul Sartre.

- Existentialism, Life, November 6, 1964, Volume 57, No. 19 ISSN 0024-3019 Published by Time Inc. P. 102-103, begins on page 86

Kierkegaard’s comparatively early and manifold philosophical and theological reception in Germany was one of the decisive factors of expanding his works’ influence and readership throughout the world. Important for the first phase of his reception in Germany was the establishment of the journal Zwischen den Zeiten (Between the Ages) in 1922 by a heterogeneous circle of Protestant theologians: Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, Rudolf Bultmann and Friedrich Gogarten. Their thought would soon be referred to as dialectical theology. At roughly the same time, Kierkegaard was discovered by several proponents of the Jewish-Christian philosophy of dialogue in Germany, namely by Martin Buber, Ferdinand Ebner, and Franz Rosenzweig. In addition to the philosophy of dialogue, existential philosophy has its point of origin in Kierkegaard and his concept of individuality. Martin Heidegger sparsely refers to Kierkegaard in Being and Time (1927), obscuring how much he owes to him.Walter Kaufmann discussed Sartre, Jaspers, and Heidegger in relation to Kierkegaard, and Kierkegaard in relation to the crisis of religion in the 1960s. Later, Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling (Series Two) and The Sickness Unto Death (Series Three) were included in the Penguin Great Ideas Series (Two and Three).

Philosophy and theology

Kierkegaard has been called a philosopher, a theologian, the Father of Existentialism, both atheistic and theistic variations, a literary critic, a social theorist, a humorist, a psychologist, and a poet. Two of his influential ideas are “subjectivity”, and the notion popularly referred to as “leap of faith”. However, the Danish equivalent to the English phrase “leap of faith” does not appear in the original Danish nor is the English phrase found in current English translations of Kierkegaard’s works. Kierkegaard does mention the concepts of “faith” and “leap” together many times in his works.

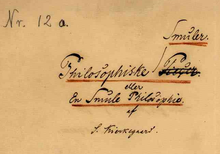

Kierkegaard’s manuscript of Philosophical Fragments

The leap of faith is his conception of how an individual would believe in God or how a person would act in love. Faith is not a decision based on evidence that, say, certain beliefs about God are true or a certain person is worthy of love. No such evidence could ever be enough to completely justify the kind of total commitment involved in true religious faith or romantic love. Faith involves making that commitment anyway. Kierkegaard thought that to have faith is at the same time to have doubt. So, for example, for one to truly have faith in God, one would also have to doubt one’s beliefs about God; the doubt is the rational part of a person’s thought involved in weighing evidence, without which the faith would have no real substance. Someone who does not realize that Christian doctrine is inherently doubtful and that there can be no objective certainty about its truth does not have faith but is merely credulous. For example, it takes no faith to believe that a pencil or a table exists, when one is looking at it and touching it. In the same way, to believe or have faith in God is to know that one has no perceptual or any other access to God, and yet still has faith in God. Kierkegaard writes, “doubt is conquered by faith, just as it is faith which has brought doubt into the world”.

Kierkegaard also stresses the importance of the self, and the self’s relation to the world, as being grounded in self-reflection and introspection. He argued in Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments that “subjectivity is truth” and “truth is subjectivity.” This has to do with a distinction between what is objectively true and an individual’s subjective relation (such as indifference or commitment) to that truth. People who in some sense believe the same things may relate to those beliefs quite differently. Two individuals may both believe that many of those around them are poor and deserve help, but this knowledge may lead only one of them to decide to actually help the poor. This is how Kierkegaard put it: “What a priceless invention statistics are, what a glorious fruit of culture, what a characteristic counterpart to the de te narratur fabula of antiquity. Schleiermacher so enthusiastically declares that knowledge does not perturb religiousness, and that the religious person does not sit safeguarded by a lightning rod and scoff at God; yet with the help of statistical tables one laughs at all of life.” In other words, Kierkegaard says: “Who has the more difficult task: the teacher who lectures on earnest things a meteor’s distance from everyday life or the learner who should put it to use?” This is how it was summed up in 1940.

Kierkegaard does not deny the fruitfulness or validity of abstract thinking (science, logic, and so on), but he does deny any superstition which pretends that abstract theorizing is a sufficient concluding argument for human existence. He holds it to be unforgivable pride or stupidity to think that the impersonal abstraction can answer the vital problems of human, everyday life. Logical theorems, mathematical symbols, physical-statistical laws can never become patters of human existence. To be human means to be concrete, to be this person here and now in this particular and decisive moment, face to face with this particular challenge. C Svere Norborg, David F. Swenson, scholar, teacher, friend. P. 20-21 Minneapolis, The University of Minnesota, 1940

Kierkegaard primarily discusses subjectivity with regard to religious matters. As already noted, he argues that doubt is an element of faith and that it is impossible to gain any objective certainty about religious doctrines such as the existence of God or the life of Christ. The most one could hope for would be the conclusion that it is probable that the Christian doctrines are true, but if a person were to believe such doctrines only to the degree they seemed likely to be true, he or she would not be genuinely religious at all. Faith consists in a subjective relation of absolute commitment to these doctrines.

Philosophical criticism

Kierkegaard’s famous philosophical 20th century critics include Theodor Adorno and Emmanuel Levinas. Non-religious philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger supported many aspects of Kierkegaard’s philosophical views, but rejected some of his religious views. One critic wrote that Adorno’s book Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic is “the most irresponsible book ever written on Kierkegaard” because Adorno takes Kierkegaard’s pseudonyms literally, and constructs a philosophy which makes him seem incoherent and unintelligible. Another reviewer says that “Adorno is from the more credible translations and interpretations of the Collected Works of Kierkegaard we have today.”

Levinas’ main attack on Kierkegaard focused on his ethical and religious stages, especially in Fear and Trembling. Levinas criticises the leap of faith by saying this suspension of the ethical and leap into the religious is a type of violence (the “leap of faith” of course, is presented by a pseudonym, thus not representing Kierkegaard’s own view, but intending to prompt the exact kind of discussion engaged in by his critics). He states: “Kierkegaardian violence begins when existence is forced to abandon the ethical stage in order to embark on the religious stage, the domain of belief. But belief no longer sought external justification. Even internally, it combined communication and isolation, and hence violence and passion. That is the origin of the relegation of ethical phenomena to secondary status and the contempt of the ethical foundation of being which has led, through Nietzsche, to the amoralism of recent philosophies.”

Levinas pointed to the Judeo-Christian belief that it was God who first commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac and that an angel commanded Abraham to stop. If Abraham were truly in the religious realm, he would not have listened to the angel’s command and should have continued to kill Isaac. To Levinas, “transcending ethics” seems like a loophole to excuse would-be murderers from their crime and thus is unacceptable. One interesting consequence of Levinas’ critique is that it seemed to reveal that Levinas viewed God as a projection of inner ethical desire rather than an absolute moral agent. However, one of Kierkegaard’s central points in Fear and Trembling was that the religious sphere entails the ethical sphere; Abraham had faith that God is always in one way or another ethically in the right, even when He commands someone to kill. Therefore, deep down, Abraham had faith that God, as an absolute moral authority, would never allow him in the end to do something as ethically heinous as murdering his own child, and so he passed the test of blind obedience versus moral choice. He was making the point that God as well as the God-Man Christ doesn’t tell people everything when sending them out on a mission and reiterated this in Stages on Life’s Way.

I conceive of God as one who approves in a calculated vigilance, I believe that he approves of intrigues, and what I have read in the sacred books of the Old Testament is not of a sort to dishearten me. The Old Testament furnishes examples abundantly of a shrewdness which is nevertheless well pleasing to God, and that at a later period Christ said to His disciples, These things I said not unto you from the beginning I have yet many things to say unto you, but ye cannot bear them now so here is a teleological suspension of the ethical rule of telling the whole truth. Soren Kierkegaard, Quidams Diary from Stages on Lifes Way, 1845 Lowrie translation 1967 p. 217-218

Sartre objected to the existence of God: If existence precedes essence, it follows from the meaning of the term sentient that a sentient being cannot be complete or perfect. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre’s phrasing is that God would be a pour-soi (a being-for-itself; a consciousness) who is also an en-soi (a being-in-itself; a thing) which is a contradiction in terms. Critics of Sartre rebutted this objection by stating that it rests on a false dichotomy and a misunderstanding of the traditional Christian view of God. Kierkegaard has Judge Vilhelm express the Christian hope this way in Either/Or,

Either, the first contains promise for the future, is the forward thrust, the endless impulse. Or, the first does not impel the individual; the power which is in the first does not become the impelling power but the repelling power, it becomes that which thrusts away. …. Thus for the sake of making a little philosophical flourish, not with the pen but with thought-God only once became flesh, and it would be vain to expect this to be repeated. Soren Kierkegaard, Either Or II 1843, p. 40-41 Lowrie Translation 1944, 1959, 1972

Sartre agreed with Kierkegaard’s analysis of Abraham undergoing anxiety (Sartre calls it anguish), but claimed that God told Abraham to do it. In his lecture, Existentialism is a Humanism, Sartre wondered whether Abraham ought to have doubted whether God actually spoke to him. In Kierkegaard’s view, Abraham’s certainty had its origin in that ‘inner voice’ which cannot be demonstrated or shown to another (“The problem comes as soon as Abraham wants to be understood”). To Kierkegaard, every external “proof” or justification is merely on the outside and external to the subject. Kierkegaard’s proof for the immortality of the soul, for example, is rooted in the extent to which one wishes to live forever.

Faith was something that Kierkegaard often wrestled with throughout his writing career; under both his real name and behind pseudonyms, he explored many different aspects of faith. These various aspects include faith as a spiritual goal, the historical orientation of faith (particularly toward Jesus Christ), faith being a gift from God, faith as dependency on a historical object, faith as a passion, and faith as a resolution to personal despair. Even so, it has been argued that Kierkegaard never offers a full, explicit and systematic account of what faith is.Either/Or was published 20 February 1843; it was mostly written during Kierkegaard’s stay in Berlin, where he took notes on Schelling’s Philosophy of Revelation. According to the Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Religion, Either/Or (vol. 1) consists of essays of literary and music criticism, a set of romantic-like-aphorisms, a whimsical essay on how to avoid boredom, a panegyric on the unhappiest possible human being, a diary recounting a supposed seduction, and (vol. II) two enormous didactic and hortatory ethical letters and a sermon. This opinion is a reminder of the type of controversy Kierkegaard tried to encourage in many of his writings both for readers in his own generation and for subsequent generations as well.

Kierkegaardian scholar Paul Holmer described Kierkegaard’s wish in his introduction to the 1958 publication of Kierkegaard’s Edifying Discourses where he wrote:

Kierkegaards constant and lifelong wish, to which his entire literature gives expression, was to create a new and rich subjectivity in himself and his readers. Unlike any authors who believe that all subjectivity is a hindrance, Kierkegaard contends that only some kinds of subjectivity are a hindrance. He sought at once to produce subjectivity if it were lacking, to correct it if it were there and needed correction, to amplify and strengthen it when it was weak and undeveloped, and, always, to bring subjectivity of every reader to the point of eligibility for Christian inwardness and concern. But the Edifying Discourses, though paralleling the pseudonymous works, spoke a little more directly, albeit without authority. They spoke the real authors conviction and were the purpose of Kierkegaards lifework. Whereas all the rest of his writing was designed to get the readers out of their lassitude and mistaken conceptions, the discourses, early and late, were the goal of the literature. Edifying Discourses: A Selection 1958 Introduction by Paul Holmer p. xviii

Later, Naomi Lebowitz explained them this way: The edifying discourses are, according to Johannes Climacus, humoristically revoked (CUP, 244, Swenson, Lowrie 1968) for unlike sermons, they are not ordained by authority. They start where the reader finds himself, in immanent ethical possibilities, aesthetic repetitions, and are themselves vulnerable to the lure of poetic sirens. They force the dialectical movements of the making and unmaking of the self before God to undergo lyrical imitations of meditation while the clefts, rifts, abysses, are everywhere to be seen.

- Noami Lebowitz, Kierkegaard A Life of Allegory 1985 p.157

Influence

The Søren Kierkegaard Statue in the Royal Library Garden in Copenhagen

Many 20th-century philosophers, both theistic and atheistic, and theologians drew concepts from Kierkegaard, including the notions of angst, despair, and the importance of the individual. His fame as a philosopher grew tremendously in the 1930s, in large part because the ascendant existentialist movement pointed to him as a precursor, although later writers celebrated him as a highly significant and influential thinker in his own right. Since Kierkegaard was raised as a Lutheran, he was commemorated as a teacher in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on 11 November and in the Calendar of Saints of the Episcopal Church with a feast day on 8 September.

Philosophers and theologians influenced by Kierkegaard are numerous and include major twentieth century theologians and philosophers.Paul Feyerabend‘s epistemological anarchism in the philosophy of science was inspired by Kierkegaard’s idea of subjectivity as truth. Ludwig Wittgenstein was immensely influenced and humbled by Kierkegaard, claiming that “Kierkegaard is far too deep for me, anyhow. He bewilders me without working the good effects which he would in deeper souls”.Karl Popper referred to Kierkegaard as “the great reformer of Christian ethics, who exposed the official Christian morality of his day as anti-Christian and anti-humanitarian hypocrisy”.Hilary Putnam admires Kierkegaard, “for his insistence on the priority of the question, ‘How should I live?'”. By the early 1930s, Jacques Ellul‘s three primary sources of inspiration were Karl Marx, Søren Kierkegaard, and Karl Barth. According to Ellul, Marx and Kierkegaard were his two greatest influences, and the only two authors of which he read all of their work.

Kierkegaard has also had a considerable influence on 20th-century literature. Figures deeply influenced by his work include W. H. Auden, Jorge Luis Borges, Don DeLillo, Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka,David Lodge, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Rainer Maria Rilke, J.D. Salinger and John Updike. What George Henry Price wrote in his 1963 book The Narrow Pass regarding the “who” and the “what” of Kierkegaard still seems to hold true today: “Kierkegaard was the sanest man of his generation….Kierkegaard was a schizophrenic….Kierkegaard was the greatest Dane….the difficult Dane….the gloomy Dane…Kierkegaard was the greatest Christian of the century….Kierkegaard’s aim was the destruction of the historic Christian faith….He did not attack philosophy as such….He negated reason….He was a voluntarist….Kierkegaard was the Knight of Faith….Kierkegaard never found faith….Kierkegaard possessed the truth….Kierkegaard was one of the damned.”

Kierkegaard had a profound influence on psychology. He is widely regarded as the founder of Christian psychology and of existential psychology and therapy. Existentialist (often called “humanistic”) psychologists and therapists include Ludwig Binswanger, Viktor Frankl, Erich Fromm, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May. May based his The Meaning of Anxiety on Kierkegaard’s The Concept of Anxiety. Kierkegaard’s sociological work Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age critiques modernity.Ernest Becker based his 1974 Pulitzer Prize book, The Denial of Death, on the writings of Kierkegaard, Freud and Otto Rank. Kierkegaard is also seen as an important precursor of postmodernism. Danish priest Johannes Møllehave has lectured about Kierkegaard. In popular culture, he was the subject of serious television and radio programmes; in 1984, a six-part documentary Sea of Faith: Television series presented by Don Cupitt featured an episode on Kierkegaard, while on Maundy Thursday in 2008, Kierkegaard was the subject of discussion of the BBC Radio 4 programme presented by Melvyn Bragg, In Our Time, during which it was suggested that Kierkegaard straddles the analytic/continental divide. Google honoured him with a Google Doodle on his 200th anniversary.

Kierkegaard is considered by some modern theologians to be the “Father of Existentialism.” Because of his influence and in spite of it, others only consider either Martin Heidegger or Jean-Paul Sartre to be the actual “Father of Existentialism.” Kierkegaard predicted his posthumous fame, and foresaw that his work would become the subject of intense study and research. In 1784 Immanuel Kant, many years before Kierkegaard, challenged the thinkers of Europe to think for themselves in a manner suggestive of Kierkegaard’s philosophy in the nineteenth century. In 1851 Arthur Schopenhauer said the same as Kierkegaard had said about the lack of realism in the reading public in Either/Or Part I and Prefaces. In 1854 Søren Kierkegaard wrote a note to “My Reader” of a similar nature.

Selected bibliography

- (1841) On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates (Om Begrebet Ironi med stadigt Hensyn til Socrates)

- (1843) Either/Or (Enten-Eller)

- (1843) Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 (To opbyggelige Taler)

- (1843) Fear and Trembling (Frygt og Bæven)

- (1843) Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 (Tre opbyggelige Taler)

- (1843) Repetition (Gjentagelsen)

- (1843) Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 (Fire opbyggelige Taler)

- (1844) Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 (To opbyggelige Taler)

- (1844) Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 (Tre opbyggelige Taler)

- (1844) Philosophical Fragments (Philosophiske Smuler)

- (1844) The Concept of Anxiety (Begrebet Angest)

- (1844) Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 (Fire opbyggelige Taler)

- (1845) Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions (Tre Taler ved tænkte Leiligheder)

- (1845) Stages on Life’s Way (Stadier paa Livets Vei)

- (1846) Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments (Afsluttende uvidenskabelig Efterskrift)

- (1847) Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits (Opbyggelige Taler i forskjellig Aand), which included Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing

- (1847) Works of Love (Kjerlighedens Gjerninger)

- (1848) Christian Discourses (Christelige Taler)

- (1848, published 1859) The Point of View of My Work as an Author “as good as finished” (IX A 293) ((Synspunktet for min Forfatter-Virksomhed. En ligefrem Meddelelse, Rapport til Historien))

- (1849) The Sickness Unto Death (Sygdommen til Døden)

- (1849) Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays ((“Ypperstepræsten” “Tolderen” “Synderinden”, tre Taler ved Altergangen om Fredagen))

- (1850) Practice in Christianity (Indøvelse i Christendom)