James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist

, geneticist and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material”. Watson earned degrees at the University of Chicago (BS, 1947) and Indiana University (PhD, 1950). Following a post-doctoral year at the University of Copenhagen with Herman Kalckar and Ole Maale, Watson worked at the University of Cambridge‘s Cavendish Laboratory in England, where he first met his future collaborator Francis Crick. From 1956 to 1976, Watson was on the faculty of the Harvard University Biology Department, promoting research in molecular biology. From 1968 he served as director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), greatly expanding its level of funding and research. At CSHL, he shifted his research emphasis to the study of cancer, along with making it a world leading research center in molecular biology. In 1994, he started as president and served for 10 years. He was then appointed chancellor, serving until he resigned in 2007 after making comments claiming a genetic link between intelligence and race. Between 1988 and 1992, Watson was associated with the National Institutes of Health, helping to establish the Human Genome Project. Watson has written many science books, including the textbook Molecular Biology of the Gene (1965) and his bestselling book The Double Helix (1968). In January 2019, following the broadcast of a television documentary in which Watson repeated his views about race and genetics, CSHL revoked honorary titles that it had awarded to him and severed all ties with him.

James D. Watson was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, as the only son of Jean (Mitchell) and James D. Watson, a businessman descended mostly from colonial English immigrants to America.[11] His mother’s father, Lauchlin Mitchell, a tailor, was from Glasgow, Scotland, and her mother, Lizzie Gleason, was the child of parents from County Tipperary, Ireland.[12] Raised Catholic, he later described himself as “an escapee from the Catholic religion.”[13] Watson said, “The luckiest thing that ever happened to me was that my father didn’t believe in God.”[14] Watson grew up on the south side of Chicago and attended public schools, including Horace Mann Grammar School and South Shore High School.[11][15] He was fascinated with bird watching, a hobby shared with his father,[16] so he considered majoring in ornithology.[17] Watson appeared on Quiz Kids, a popular radio show that challenged bright youngsters to answer questions.[18] Thanks to the liberal policy of University president Robert Hutchins, he enrolled at the University of Chicago, where he was awarded a tuition scholarship, at the age of 15.[11][17][19] After reading Erwin Schrdinger‘s book What Is Life? in 1946, Watson changed his professional ambitions from the study of ornithology to genetics.[20] Watson earned his BS degree in Zoology from the University of Chicago in 1947.[17] In his autobiography, Avoid Boring People, Watson described the University of Chicago as an “idyllic academic institution where he was instilled with the capacity for critical thought and an ethical compulsion not to suffer fools who impeded his search for truth”, in contrast to his description of later experiences. In 1947 Watson left the University of Chicago to become a graduate student at Indiana University, attracted by the presence at Bloomington of the 1946 Nobel Prize winner Hermann Joseph Muller, who in crucial papers published in 1922, 1929, and in the 1930s had laid out all the basic properties of the heredity molecule that Schrdinger presented in his 1944 book.[21] He received his PhD degree from Indiana University in 1950; Salvador Luria was his doctoral advisor.[17][22]

Originally, Watson was drawn into molecular biology by the work of Salvador Luria. Luria eventually shared the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the Luria-Delbrck experiment, which concerned the nature of genetic mutations. He was part of a distributed group of researchers who were making use of the viruses that infect bacteria, called bacteriophages. He and Max Delbrck were among the leaders of this new “Phage Group,” an important movement of geneticists from experimental systems such as Drosophila towards microbial genetics. Early in 1948, Watson began his PhD research in Luria’s laboratory at Indiana University.[22] That spring, he met Delbrck first in Luria’s apartment and again that summer during Watson’s first trip to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL).[23][24] The Phage Group was the intellectual medium where Watson became a working scientist. Importantly, the members of the Phage Group sensed that they were on the path to discovering the physical nature of the gene. In 1949, Watson took a course with Felix Haurowitz that included the conventional view of that time: that genes were proteins and able to replicate themselves.[25] The other major molecular component of chromosomes, DNA, was widely considered to be a “stupid tetranucleotide,” serving only a structural role to support the proteins.[26] Even at this early time, Watson, under the influence of the Phage Group, was aware of the Avery-MacLeod-McCarty experiment, which suggested that DNA was the genetic molecule. Watson’s research project involved using X-rays to inactivate bacterial viruses.[27] Watson then went to Copenhagen University in September 1950 for a year of postdoctoral research, first heading to the laboratory of biochemist Herman Kalckar.[11] Kalckar was interested in the enzymatic synthesis of nucleic acids, and he wanted to use phages as an experimental system. Watson wanted to explore the structure of DNA, and his interests did not coincide with Kalckar’s.[28] After working part of the year with Kalckar, Watson spent the remainder of his time in Copenhagen conducting experiments with microbial physiologist Ole Maale, then a member of the Phage Group.[29] The experiments, which Watson had learned of during the previous summer’s Cold Spring Harbor phage conference, included the use of radioactive phosphate as a tracer to determine which molecular components of phage particles actually infect the target bacteria during viral infection.[28] The intention was to determine whether protein or DNA was the genetic material, but upon consultation with Max Delbrck,[28] they determined that their results were inconclusive and could not specifically identify the newly labeled molecules as DNA.[30] Watson never developed a constructive interaction with Kalckar, but he did accompany Kalckar to a meeting in Italy, where Watson saw Maurice Wilkins talk about his X-ray diffraction data for DNA.[11] Watson was now certain that DNA had a definite molecular structure that could be elucidated.[31] In 1951, the chemist Linus Pauling in California published his model of the amino acid alpha helix, a result that grew out of Pauling’s efforts in X-ray crystallography and molecular model building. After obtaining some results from his phage and other experimental research[32] conducted at Indiana University, Statens Serum Institut (Denmark), CSHL, and the California Institute of Technology, Watson now had the desire to learn to perform X-ray diffraction experiments so he could work to determine the structure of DNA. That summer, Luria met John Kendrew,[33] and he arranged for a new postdoctoral research project for Watson in England.[11] In 1951 Watson visited the Stazione Zoologica ‘Anton Dohrn’ in Naples.[34] In mid-March 1953, Watson and Crick deduced the double helix structure of DNA.[11] Crucial to their discovery were the experimental data collected at King’s College London — mainly by Rosalind Franklin, under the supervision of Maurice Wilkins.[35] Sir Lawrence Bragg,[36] the director of the Cavendish Laboratory (where Watson and Crick worked), made the original announcement of the discovery at a Solvay conference on proteins in Belgium on April 8, 1953; it went unreported by the press. Watson and Crick submitted a paper entitled Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid to the scientific journal Nature, which was published on April 25, 1953.[37] Bragg gave a talk at the Guy’s Hospital Medical School in London on Thursday, May 14, 1953, which resulted in a May 15, 1953, article by Ritchie Calder in the London newspaper News Chronicle, entitled “Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life.” Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Dorothy Hodgkin, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M. Oughton were some of the first people in April 1953 to see the model of the structure of DNA, constructed by Crick and Watson; at the time, they were working at Oxford University‘s Chemistry Department. All were impressed by the new DNA model, especially Brenner, who subsequently worked with Crick at Cambridge in the Cavendish Laboratory and the new Laboratory of Molecular Biology. According to the late Beryl Oughton, later Rimmer, they all travelled together in two cars once Dorothy Hodgkin announced to them that they were off to Cambridge to see the model of the structure of DNA.[38] The Cambridge University student newspaper Varsity also ran its own short article on the discovery on Saturday, May 30, 1953. Watson subsequently presented a paper on the double-helical structure of DNA at the 18th Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Viruses in early June 1953, six weeks after the publication of the Watson and Crick paper in Nature. Many at the meeting had not yet heard of the discovery. The 1953 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium was the first opportunity for many to see the model of the DNA double helix. Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for their research on the structure of nucleic acids.[11][11][39][40] Rosalind Franklin had died in 1958 and was therefore ineligible for nomination.[35] The publication of the double helix structure of DNA has been described as a turning point in science; understanding of life was fundamentally changed and the modern era of biology began.[41] Watson and Crick’s use of DNA X-ray diffraction data collected by Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling was unauthorized. They used some of her unpublished datawithout her consentin their construction of the double helix model of DNA.[35][42] Franklin’s results provided estimates of the water content of DNA crystals and these results were consistent with the two sugar-phosphate backbones being on the outside of the molecule. Franklin told Crick and Watson that the backbones had to be on the outside; before then, Linus Pauling and Watson and Crick had erroneous models with the chains inside and the bases pointing outwards.[21] Her identification of the space group for DNA crystals revealed to Crick that the two DNA strands were antiparallel. The X-ray diffraction images collected by Gosling and Franklin provided the best evidence for the helical nature of DNA. Watson and Crick had three sources for Franklin’s unpublished data: According to one critic, Watson’s portrayal of Franklin in The Double Helix was negative and gave the appearance that she was Wilkins’ assistant and was unable to interpret her own DNA data.[46] The accusation was indefensible since Franklin told Crick and Watson that the helix backbones had to be on the outside.[21] A review of the correspondence from Franklin to Watson, in the archives at CSHL, revealed that the two scientists later exchanged constructive scientific correspondence. Franklin consulted with Watson on her tobacco mosaic virus RNA research. Franklin’s letters began on friendly terms with “Dear Jim”, and concluded with equally benevolent and respectful sentiments such as “Best Wishes, Yours, Rosalind”. Each of the scientists published their own unique contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA in separate articles, and all of the contributors published their findings in the same volume of Nature. These classic molecular biology papers are identified as: Watson J.D. and Crick F.H.C. “A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid” Nature 171, 737-738 (1953);[37] Wilkins M.H.F., Stokes A.R. & Wilson, H.R. “Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids” Nature 171, 738-740 (1953);[47] Franklin R. and Gosling R.G. “Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate” Nature 171, 740-741 (1953).[48] In 1956, Watson accepted a position in the Biology department at Harvard University. His work at Harvard focused on RNA and its role in the transfer of genetic information.[49] He championed a switch in focus for the school from classical biology to molecular biology, stating that disciplines such as ecology, developmental biology, taxonomy, physiology, etc. had stagnated and could progress only once the underlying disciplines of molecular biology and biochemistry had elucidated their underpinnings, going so far as to discourage their study by students. Watson continued to be a member of the Harvard faculty until 1976, even though he took over the directorship of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1968.[49] Views on Watson’s scientific contributions while at Harvard are somewhat mixed. His most notable achievements in his two decades at Harvard may be what he wrote about science, rather than anything he discovered during that time.[50] Watson’s first textbook, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, set a new standard for textbooks, particularly through the use of concept headsbrief declarative subheadings.[51] His next textbook was Molecular Biology of the Cell, in which he coordinated the work of a group of scientist-writers. His third textbook was Recombinant DNA, which described the ways in which genetic engineering has brought much new information about how organisms function. The textbooks are still in print. In 1968, Watson wrote The Double Helix,[52] listed by the Board of the Modern Library as number seven in their list of 100 Best Nonfiction books.[53] The book details the story of the discovery of the structure of DNA, as well as the personalities, conflicts and controversy surrounding their work, and includes many of his private emotional impressions at the time. Watson’s original title was to have been “Honest Jim”.[54] Some controversy surrounded the publication of the book. Watson’s book was originally to be published by the Harvard University Press, but Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins objected, among others. Watson’s home university dropped the project and the book was commercially published.[55][56] During his tenure at Harvard, Watson participated in a protest against the Vietnam War, leading a group of 12 biologists and biochemists calling for “the immediate withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam.”[57] In 1975, on the thirtieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, Watson was one of over 2000 scientists and engineers who spoke out against nuclear proliferation to President Gerald Ford, arguing that there was no proven method for the safe disposal of radioactive waste, and that nuclear plants were a security threat due to the possibility of terrorist theft of plutonium.[58] External video In 1968, Watson became the Director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). Between 1970 and 1972, the Watsons’ two sons were born, and by 1974, the young family made Cold Spring Harbor their permanent residence. Watson served as the laboratory’s director and president for about 35 years, and later he assumed the role of chancellor and then Chancellor Emeritus. In his roles as director, president, and chancellor, Watson led CSHL to articulate its present-day mission, “dedication to exploring molecular biology and genetics in order to advance the understanding and ability to diagnose and treat cancers, neurological diseases, and other causes of human suffering.”[59] CSHL substantially expanded both its research and its science educational programs under Watson’s direction. He is credited with “transforming a small facility into one of the world’s great education and research institutions. Initiating a program to study the cause of human cancer, scientists under his direction have made major contributions to understanding the genetic basis of cancer.”[60] In a retrospective summary of Watson’s accomplishments there, Bruce Stillman, the laboratory’s president, said, “Jim Watson created a research environment that is unparalleled in the world of science.”[60] In 2007, Watson said, “I turned against the left wing because they don’t like genetics, because genetics implies that sometimes in life we fail because we have bad genes. They want all failure in life to be due to the evil system.”[61] In 1994, Watson became President of CSHL. Francis Collins took over the role as Director of the Human Genome Project. He was quoted in The Sunday Telegraph in 1997 as stating: “If you could find the gene which determines sexuality and a woman decides she doesn’t want a homosexual child, well, let her.”[64] The biologist Richard Dawkins wrote a letter to The Independent claiming that Watson’s position was misrepresented by The Sunday Telegraph article, and that Watson would equally consider the possibility of having a heterosexual child to be just as valid as any other reason for abortion, to emphasise that Watson is in favor of allowing choice.[65] On the issue of obesity, Watson was quoted in 2000, saying: “Whenever you interview fat people, you feel bad, because you know you’re not going to hire them.”[66] Watson has repeatedly supported genetic screening and genetic engineering in public lectures and interviews, arguing that stupidity is a disease and the “really stupid” bottom 10% of people should be cured.[67] He has also suggested that beauty could be genetically engineered, saying in 2003, “People say it would be terrible if we made all girls pretty. I think it would be great.”[67][68] In 2007, James Watson became the second person[69] to publish his fully sequenced genome online,[70] after it was presented to him on May 31, 2007, by 454 Life Sciences Corporation[71] in collaboration with scientists at the Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine. Watson was quoted as saying, “I am putting my genome sequence on line to encourage the development of an era of personalized medicine, in which information contained in our genomes can be used to identify and prevent disease and to create individualized medical therapies”.[72][73][74]Overview

Early Life and Education

Career and Research

Luria, Delbrck, and the Phage Group

Identifying the double helix

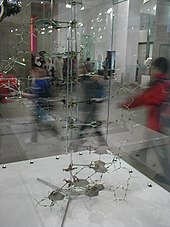

DNA model built by Crick and Watson in 1953, on display in the Science Museum, London

DNA model built by Crick and Watson in 1953, on display in the Science Museum, London Watson’s accomplishment is displayed on the monument at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Because the monument memorializes only American laureates, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins (who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) are omitted.

Watson’s accomplishment is displayed on the monument at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Because the monument memorializes only American laureates, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins (who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) are omitted.Use of the King’s College results

Harvard University

Publishing The Double Helix

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

![]() James Watson: Why society isn’t ready for genomic-based medicine, 2012, Chemical Heritage Foundation

James Watson: Why society isn’t ready for genomic-based medicine, 2012, Chemical Heritage FoundationHuman Genome Project

In 1990, Watson was appointed as the Head of the Human Genome Project at the National Institutes of Health, a position he held until April 10, 1992.[62] Watson left the Genome Project after conflicts with the new NIH Director, Bernadine Healy. Watson was opposed to Healy’s attempts to acquire patents on gene sequences, and any ownership of the “laws of nature.” Two years before stepping down from the Genome Project, he had stated his own opinion on this long and ongoing controversy which he saw as an illogical barrier to research; he said, “The nations of the world must see that the human genome belongs to the world’s people, as opposed to its nations.” He left within weeks of the 1992 announcement that the NIH would be applying for patents on brain-specific cDNAs.[63] (The issue of the patentability of genes has since been resolved in the US by the US Supreme Court; see Association for Molecular Pathology v. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office)